自定義按鈕動態變化

I read Bari Weiss’ resignation letter from the New York Times with some perplexity. In particular, I found her claim that she “was hired with the goal of bringing in voices that would not otherwise appear in your pages” a bit strange: Weiss is, after all, a wealthy graduate of Columbia who’s lived in the Northeast her entire life.

我有些困惑地讀了《紐約時報》上巴里·韋斯的辭職信。 尤其是,我發現她聲稱她“被錄用的目的是使您的聲音不會出現在您的頁面中”有點奇怪:Weiss畢竟是哥倫比亞的一位富有的畢業生,她整個居住在東北。生活。

I’ve been playing around with New York Times archive data for some time and wanted to test Weiss’ claim. Has there been a (quantitative) change in the news the New York Times produces, especially since November 2016?

我一直在玩《紐約時報》的存檔數據已有一段時間,想測試一下魏斯的說法。 《紐約時報》產生的新聞是否有(定量)變化,尤其是自2016年11月以來?

In this post, I’m going to take a look at what we can learn about “all the news that’s fit to print” from the metadata available in the archive — things like word counts, bylines, and news divisions. I’m looking for ways to approximate the “diversity” of the Times’ coverage since 2015. Essentially, we’re looking for real evidence of all those reporters sent to diners in Trump country in 2016 and after.

在這篇文章中,我將看一下我們可以從檔案庫中可用的元數據中了解“適合打印的所有新聞”的內容,例如字數統計,署名和新聞劃分。 自2015年以來,我一直在尋找逼近《紐約時報》報道“多樣性”的方法。從本質上講,我們正在尋找2016年及之后派往特朗普國家食客的所有記者的真實證據。

(For reference, here’s a map of all the IHOPs in the country. IHOP seemed like a good proxy for diners generally, and Waffle House is too concentrated in the south to be meaningful nationwide — it’s actually not that far off from what we have.)

(作為參考,下面是該國所有IHOP的地圖。IHOP似乎通常是食客的一個很好的代理,Waffle House太集中在南部,在全國范圍內都沒有意義-實際上距離我們所擁有的并不遙遠。 )

The New York Times, as the largest and most successful American newspaper (and as far as I can tell, the biggest one with a publicly available API) offers an interesting case for analysis: the Times went to a paywall in 2011, and its emphasis on producing content to fuel subscriptions has accelerated since then; simultaneously, engagement with the Times since Trump’s election has increased steadily. Bari Weiss aside, how has the Times navigated its way through competing currents in media?

《紐約時報》作為最大,最成功的美國報紙(據我所知,是最大的擁有公開API的報紙)提供了一個有趣的分析案例:《紐約時報》于2011年進入付費專欄,其重點是從那時起,為訂閱提供內容的制作速度加快了; 同時,自特朗普當選以來與《紐約時報》的參與穩步增加。 除了巴里·魏斯(Bari Weiss),《紐約時報》如何駕馭媒體競爭潮流?

適合打印 (Fit to Print)

Let’s first look at the Times’ output in broad terms. The Times itself reported a 42% increase in the number of paid (digital) subscriptions between December 2016 and December 2017. Certainly not all of that is attributable to Trump (we can gesture at secular media trends and the effectiveness of the Times’ own strategy there), but some of it certainly is due to Trump: the Times told CNBC in November 2016 that they had seen startling subscriber growth in the three weeks since the election, and the times rode that increase to the 42% year over year subscriber growth between 2016 and 2017 cited in their 2017 10-K.

讓我們首先從廣義上看《紐約時報》的產出。 《泰晤士報》本身報告稱,2016年12月至2017年12月之間,付費(數字)訂閱數量增長了42%。當然,并非所有這一切都應歸功于特朗普(我們可以對世俗媒體趨勢以及《 泰晤士報》自身戰略的有效性進行指責)有),但有些可以肯定的是 ,由于特朗普:時代在接受CNBC在2016年11月,他們曾看見,因為大選驚心在為期三周的用戶增長,與時代騎馬走過一年的用戶增長是提高到42%,比去年在其2017年10-K中引用的2016年至2017年之間。

技術說明 (Technical Notes)

I’ve used the Times’ archive API to download all the available data, going back to January of 2015. I wrote a class to handle this for me, but the script is relatively simple: call the API, parse the JSON, save as a CSV, and repeat for each year, for each month. Because we get a full month’s archive with each API call, we should fall well under the rate limit of 4,000 calls per day.

我使用Times的存檔API下載了所有可用數據,可追溯到2015年1月。我為我編寫了一個類來處理此數據,但腳本相對簡單:調用API,解析JSON,另存為CSV,然后每年重復一次,每月重復一次。 因為每個API調用都會獲得一個月的存檔,所以我們應該將其限制在每天4,000個調用的速率限制之下。

The code I used to extract the archive is available at my github, here. The full script, an exercise in data engineering, will also allow you to post the archive to a relational database (Redshift on AWS in this case), but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

我用來提取檔案的代碼可在我的github上找到 。 完整的腳本(數據工程中的練習)還將允許您將存檔發布到關系數據庫(在本例中為AWS上的Redshift),但這超出了本文的范圍。

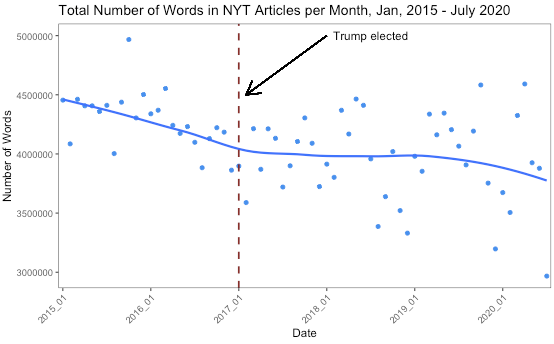

We can see that the overall output (in terms of stories published) has been decreasing over time:

我們可以看到,隨著時間的流逝,總體產出(就已發表的故事而言)一直在下降:

Trump’s election does not appear to have had any effect here — the Times has steadily dropped the number of articles it’s published going back to 2015.

特朗普的當選似乎并未在此產生任何影響-泰晤士報已將其可追溯至2015年的文章數量穩步下降。

Is this true across all news desks at the paper? Or across all sections (i.e. politics, U.S. news, international news, etc.)?

在報紙上的所有新聞服務臺上都是這樣嗎? 還是所有部分(例如政治,美國新聞,國際新聞等)?

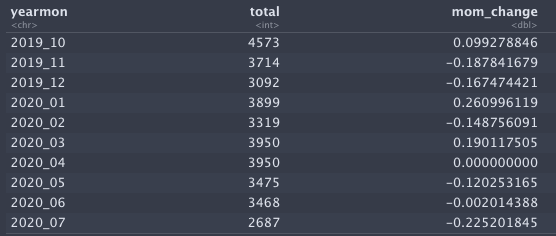

Nothing jumps out from the chart, rather there’s a general across different sections of the paper. In terms of real numbers, across the top sections of the paper (i.e. the sections under which the most articles are published) the full table is available in the github repo, the last 10 months’ of aggregate data looks like this (throw out the last row as potentially incomplete):

圖表上什么都沒有跳出來,而是本文的不同部分都有一個概括。 就實數而言,在論文的頂部(即發布文章最多的部分)中,完整表可在github存儲庫中找到,最后10個月的匯總數據如下所示(將最后一行可能不完整):

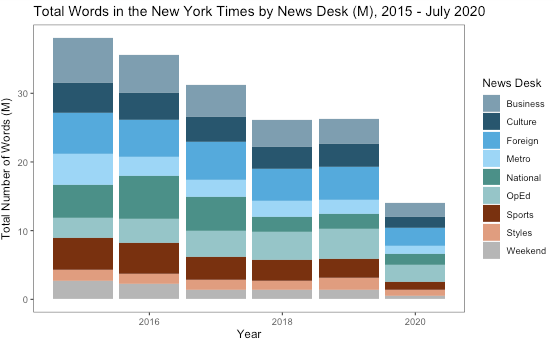

But perhaps there’s more to the story than declining “output.” If we look not at the number of articles, but at the number of words devoted to each section, we can see where that output has gone. I’ve tallied the average word count by year in the following table:

但是,也許故事的內容不僅僅是減少“產出”。 如果我們不看文章的數量,而是看每個部分的單詞數,我們可以看到輸出結果。 我在下表中按年份統計了平均單詞數:

So there are fewer articles being published, but those that make it to print (or the website) tend to be longer — growing at an average of about 7.5% every year.

因此,發表的文章較少,但可打印的文章(或網站)則往往更長-每年平均增長約7.5%。

The table below shows the top sections in every year since 2015, as well as the word count for all the articles published in each section. I’ve included the year over year change as well. (I should note that for 2020 articles I’ve prorated the output, so that although only 7 months of 2020 are fully available for analysis, we should be able to compare 2020 rates with other years available in the dataset.)

下表顯示了自2015年以來每年的熱門部分,以及每個部分中發布的所有文章的字數。 我還包括了逐年變化。 (我應該注意,對于2020年的文章,我已經按比例對輸出進行了估算,因此,盡管只有2020年的7個月可以完全用于分析,但我們應該能夠將2020年的比率與數據集中的其他年份進行比較。)

We can look at this data graphically, too:

我們也可以以圖形方式查看此數據:

And using the same analysis we did for the articles above:

并使用與上述文章相同的分析方法:

Some things stand out: as we’ve seen, it looks like the decline in the paper’s “output” is general, rather than particular. Most of the sections are down, albeit modestly. In all, the Times publishes about 45.5 million words each year. This has fallen slightly since 2015, by about 2.5% each year.

有些事情脫穎而出:如我們所見,論文的“產出”下降似乎是普遍的,而不是特殊的。 大多數部分都下降了,盡管幅度不大。 總體而言,《泰晤士報》每年出版約4550萬個單詞。 自2015年以來,這一數字每年略有下降,約為2.5%。

What we see is generally in line with our previous findings: there is some evidence of less content in fewer articles and fewer words, but those forces are generally working against one another—the Times is producing less, but more detailed content as part of a secular shift in strategy, from a business based on advertising to one based on digital subscriptions.

我們所看到的通常與我們以前的發現相符:有證據表明,文章較少,字詞較少,但這些力量總體上是相互抵觸的。戰略的長期轉變,從基于廣告的業務向基于數字訂閱的業務轉變。

With these longer, more detailed pieces, the Times might have more room to send journalists to Trump country diners. Do we see that in their coverage?

有了這些更長,更詳細的文章,《紐約時報》可能有更大的空間將記者派往特朗普的鄉村食客。 我們在他們的報道中看到了嗎?

不寬容的政治 (The Politics of Intolerance)

So, what was the Times covering in 2015? What was it covering then that it isn’t now, and what is it covering now that it wasn’t then?

那么,《泰晤士報》 2015年報道的內容是什么? 當時不是現在涵蓋了什么,現在還沒有涵蓋什么?

We can look at this in a few ways. In this piece I’m going to look at the geography of coverage (at least, what I could find from some simple text mining), but some others include text analysis of both headlines and keywords, or looking at bylines and representation at the Times in more detail.

我們可以通過幾種方式對此進行研究。 在本篇文章中,我將研究覆蓋范圍的地理位置(至少,我可以從一些簡單的文本挖掘中找到),但另一些則包括標題和關鍵字的文本分析,或者在《泰晤士報》上查看下劃線和代表形式。更詳細地。

技術說明 (Technical notes)

I’ve generated the data under analysis by parsing bylines in archived articles. This is, as far as I can tell, the easiest way to get geography from historical articles. The Times does offer a wire service that includes geographical information, but what I’m interested in here is historical data, not incoming stories.

我已經通過分析存檔文章中的按行生成了正在分析的數據。 據我所知,這是從歷史文章中獲取地理信息的最簡單方法。 時報確實提供了包括地理信息在內的有線服務,但是我在這里感興趣的是歷史數據,而不是傳入的故事。

The script I use to parse geography relies on the journalistic convention of the dateline — something like KABUL, Afghanistan; LONDON; or, as in one recent article, CENTER OF THE WORLD, Ohio (in an article about Ohio State football). Given the available data, this seemed like the best (/only) way to get the information we’re interested in.

我用來解析地理的腳本依賴于時間軸的新聞慣例-諸如阿富汗的卡布爾(KABUL); 倫敦; 或者,如最近的一篇文章 ,《俄亥俄州的世界中心》(關于俄亥俄州立足球的一篇文章)。 給定可用數據,這似乎是獲取我們感興趣的信息的最佳(/唯一)方法。

A few caveats to this approach: articles that have a dateline like this are less and less common, not only at the Times but elsewhere in the news media as well. In many cases, we also miss out on geographic information from the dateline because there’s no geographic focus to the article — think opinion pieces, magazine posts, podcasts and other multimedia posts, as well as “geographically diffuse” stories about things like the coronavirus, or Biden’s VP pick.

這種方法的一些注意事項:帶有這樣的日期期限的文章越來越少見,不僅在《紐約時報》,而且在新聞媒體的其他地方也是如此。 在許多情況下,我們也錯過了日期欄中的地理信息,因為該文章沒有針對地理區域的關注-思考文章,雜志文章,播客和其他多媒體文章,以及關于諸如冠狀病毒,或拜登(Biden)的VP選擇。

More specifically, if we look at the number of articles with extractable geographic information by year, we have the following:

更具體地說,如果按年份查看具有可提取的地理信息的文章數,則將具有以下內容:

Not surprising, given that we know the number of stories overall is decreasing. But the same is true if we look at these kinds of stories as a percentage of all stories published, we get a clearer picture:

并不奇怪,因為我們知道故事的數量整體減少。 但是,如果我們將這些類型的故事占所有已發布故事的百分比來看,情況也是如此,我們會得到更清晰的畫面:

Looks like the percentage of stories with identifiable geography in the byline has remained roughly constant with a dip in 2018.

看起來在地標中具有可識別地理位置的故事百分比在2018年有所下降,大致保持不變。

This suggests a few things: first, that there may have been a shift to more named places after Trump’s election (2017 has the highest percentage of “geographic” bylines at 28.5%) but it wasn’t major (the average was 26% of bylines containing geographic information). Second, though we’ve seen the Times drop the overall number of articles, they don’t seem to have shifted significantly away from “locatable” stories.

這表明了一些事情:首先,特朗普當選后可能已經轉移到了更具名的地方(2017年“地理”署名的比例最高,為28.5%),但并不是主要的(平均值為26%包含地理信息的摘要)。 其次,盡管我們已經看到《紐約時報》減少了文章的總數,但是它們似乎并沒有明顯偏離“可定位”的故事。

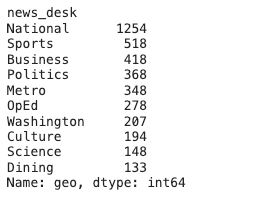

There’s one more thing we should look at with these aggregate measures: which sections are the most “diverse?” By “diversity” here I mean place diversity, without reference to the subjects or authors of the pieces in question (that material should be saved for a future analysis). I’m going to exclude foreign desk coverage here—it’s natural that a desk with a remit to cover stories from all over the world would feature articles from… all over the world—and focus on domestic stories. So, what does the diversity by news desk look like?

通過這些總體衡量指標,我們還需要考慮另一件事:哪些部分最“多樣化”? 這里所說的“多樣性”是指地點多樣性,而不涉及所討論作品的主題或作者(應保存材料以備將來分析)。 我將在這里排除國外的報道范圍,自然而然的是,一個具有職權范圍以報道來自世界各地的故事的辦公桌將收錄來自……世界各地的文章,并將重點放在國內故事上。 那么,新聞臺的多樣性是什么樣的呢?

And finally, what is the count of unique places by year?

最后,按年計算的不重復地點數是多少?

(Note that the 2020 number is low because we’re only halfway through the year. On a pro-rated basis, 451 places would translate to about 770 locations, putting 2020 in line with 2019.) It would seem that the Weiss was wrong about the Times’ direction (or at least, her hire didn’t exactly presage a new era of geographic diversity in their pages).

(請注意,2020年的數字很低,因為我們還只是今年的一半。按比例計算,451個位置將轉換為大約770個位置,使2020年與2019年保持一致。)Weiss似乎是錯誤的關于《紐約時報》的發展方向(至少,她的聘用并沒有預示著他們頁面上地理多樣性的新時代)。

First let’s look worldwide.

首先讓我們放眼全球。

On to the mapping. A first quick look at the distribution of (unique) byline geography looks ecumenical enough. The distribution is, naturally enough, concentrated in the United States (although looks like maybe there is no news made in Idaho or eastern New Mexico), Europe, and the Pacific Rim. (Note that this distribution is roughly the same one you might find from any other big news organization — this chart from a 2018 Forbes article shows the distribution of stories on CNN, Fox, and MSNBC).

到映射。 快速瀏覽一下(獨特的)按行標注地理分布看起來足夠普遍。 分布自然就集中在美國(盡管看起來在愛達荷州或新墨西哥州東部可能沒有新聞),歐洲和環太平洋地區。 (請注意,這種分布與您從其他大型新聞機構可能發現的分布大致相同-來自福布斯 2018年文章的這張圖表顯示了CNN,Fox和MSNBC的新聞分布)。

What happens if we zoom in on the United States, and look at year over year changes? For this part, I’ve filtered the data down to include the United States. only. Let’s see what we have.

如果我們放大美國,看看逐年變化會怎樣? 對于這一部分,我已經過濾掉數據以包括美國。 只要。 讓我們看看我們有什么。

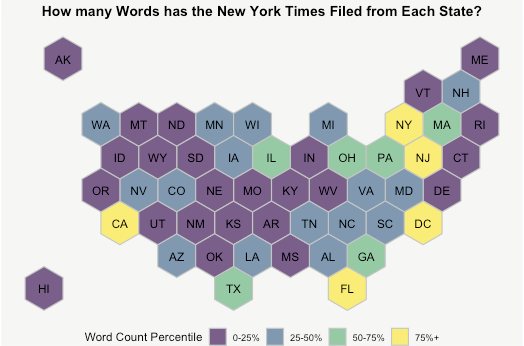

Some things stand out here: we have lots of coverage in the big cities — New York, DC, Los Angeles, Chicago (though we might expect more news about places closer to New York — commuters from Connecticut would be interested in the Metro section, for example) but five red states, Ohio, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Georgia and Florida, get a lot of coverage as well.

這里有一些突出的地方:我們在大城市(紐約,哥倫比亞特區,洛杉磯,芝加哥)提供了很多報道(盡管我們可能希望獲得更多靠近紐約的新聞,而來自康涅狄格州的通勤者會對“地鐵”部分感興趣,例如),但五個紅色州(俄亥俄州,愛荷華州,賓夕法尼亞州,喬治亞州和佛羅里達州)的覆蓋率也很高。

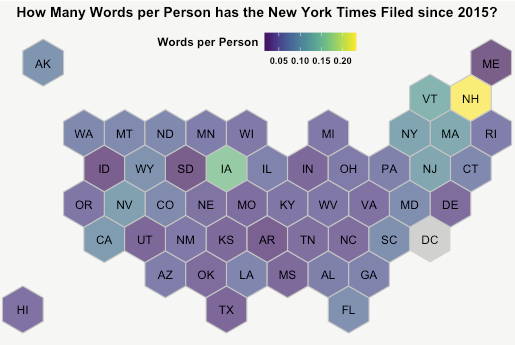

What about on a per-capita basis? Here, I’m using 2019 state population estimates from Wikipedia.

那么人均呢? 在這里,我使用的是Wikipedia的 2019年州人口估計。

I left D.C. out because it was such an outlier it threw the rest of the map off. This is what we’d expect from political coverage especially—Iowa and New Hampshire get tons of coverage in presidential election years, enough to make them stand out across the entire sample.

我把DC排除在外了,因為它離得太遠了,它把地圖的其余部分都扔掉了。 這是我們特別希望從政治報道中獲得的結果—愛荷華州和新罕布什爾州在總統選舉年獲得了大量報道,足以使他們在整個樣本中脫穎而出。

One more hex map. What if we exclude political coverage? Here I’m filtering out all stories from the politics news desk.

一張十六進制地圖。 如果我們排除政治報道該怎么辦? 在這里,我從politics新聞臺過濾掉所有故事。

Generally pretty similar, but we see some more emphasis on the Northeast, but still a lot of coverage of California, and, strangely, New Hampshire.

通常情況下非常相似,但我們看到的更多是對東北的關注,但對加利福尼亞以及新罕布什爾州的報道仍然很多。

For a closer look at the impact of Trump’s election, we can look at the data from 2015–2018. Are there any changes we can see in the map over time?

為了更深入地了解特朗普當選的影響,我們可以看看2015-2018年的數據。 隨著時間的推移,我們在地圖上可以看到任何變化嗎?

We can see a lot more action in some of the swing states in election years. 2018 and 2016 in particular show a broader range of states covered in the Times’ pages.

在選舉年的某些搖擺州中,我們可以看到更多的行動。 特別是2018年和2016年,《紐約時報》頁面涵蓋的州范圍更廣。

進一步的考慮 (Further considerations)

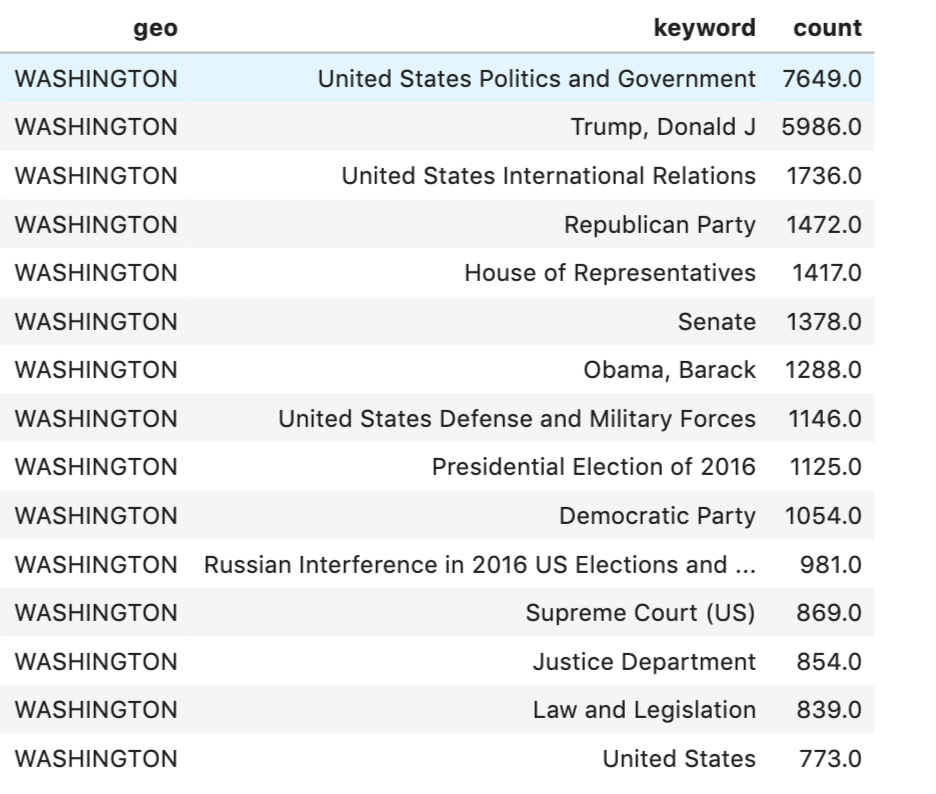

Next we should look at what the Times is writing about in each of these places. In other words, what are the keywords most associated with each state?

接下來,我們應該看一下《紐約時報》在每個地方所寫的內容。 換句話說,與每個州最相關的關鍵字是什么?

Let’s start with Washington, D.C., which sees the most Times coverage.

讓我們從華盛頓特區開始,它是《紐約時報》報道最多的地區。

As we’d expect, politics, and in particular Trump, dominate Washington coverage. It’s further not surprising that the Republicans get more coverage than democrats, since they control the Senate, White House, and Supreme Court (all of which are also featured prominently).

如我們所料,政治,特別是特朗普,主導了華盛頓的報道。 共和黨人比民主黨人擁有更多的報道也就不足為奇了,因為他們控制著參議院,白宮和最高法院(所有這些都在顯著位置)。

And what if we look at “diner country,” that is, states in the middle of the country where we’d already identified lots of Times coverage? Here’s what we have for Ohio:

如果我們看“吃飯的國家”,即我們已經確定了很多《紐約時報》報道的國家中部的州,該怎么辦? 這是俄亥俄州的設施:

And Iowa:

和愛荷華州:

And finally, Pennsylvania:

最后,賓夕法尼亞州:

It certainly does look like the Times invested heavily in coverage of 2016 swing states and covered the aftermath of the election. Curiously though, the Sports section also appears to be a major driver of “place diversity” in the Times’ coverage.

看起來《紐約時報》確實確實花了很多錢來報道2016年的搖擺狀態,并報道了選舉的后果。 令人奇怪的是,體育版塊似乎也是《紐約時報》報道中“場所多樣性”的主要推動力。

加起來 (Summing up)

So, have we found any evidence of diner journalism in the Times’ pages? Well, sure, some. It is true that, especially in election years, swing states in “flyover country” get more attention. In general, the Times looks more or less like any other big news organization, focusing on the major cities in the United States, especially in the Northeast. If you live in New Hampshire, you have the good fortune of having the most words per capita written about your state by the Times.

那么,我們是否在《泰晤士報》的網頁上找到任何關于晚餐新聞的證據? 好吧,當然。 確實,尤其是在選舉年中,“立交橋國家”中的搖擺州得到了更多關注。 總體而言,《紐約時報》看起來或多或少像其他任何大型新聞機構,都集中在美國的主要城市,尤其是東北地區。 如果您居住在新罕布什爾州,那么您的幸運之星就是,《紐約時報》以人均字數最多的是您的州。

There may be some truth to what Weiss wrote in her resignation letter; the Times does, especially in election years, spread its coverage out to states across the country. We’d expect nothing less of a national news organization. However, we’ve also seen that fewer and fewer unique places are getting covered by the Times, albeit the articles that are being produced now are longer than in years past.

魏斯在辭職信中寫的話可能有些道理。 《泰晤士報》確實將其報道范圍擴大到全國各州,尤其是在選舉年代。 我們期待有一個國家新聞機構。 但是,我們還發現,《紐約時報》報道的獨特場所越來越少,盡管現在制作的文章比過去幾年更長。

In all, the New York Times really does produce news from all over the globe and all over the United States; I’d add that the Times has also committed itself to a diversity of voices on its op-ed page, and had done so before they hired Bari Weiss; the Times has long had (dishonest) conservatives on its payroll, elevating voices that would otherwise be heard in, say, the pages of the New York Post. (The Times also proclaims that it is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor in its op-ed pages.)

總之,《紐約時報》確實確實產生了來自全球和美國各地的新聞; 我要補充的是,《泰晤士報》在其專欄文章上也致力于表達各種聲音,并且在雇用Bari Weiss之前就這樣做了。 《泰晤士報》長期以來一直( 不誠實地 )在工資單上采取保守措施,提高了人們的聲音,這些聲音本來可以在《紐約郵報》的頁面上聽到。 (《泰晤士報》還宣稱,它將致力于在其專著的頁面上向編輯發布各種信函。)

I haven’t discussed another important aspect of diversity at the New York Times: the identities of the people producing and gatekeeping the stories that get written. This is, I would argue, just as important as any focus on geographic representation, and requires a deeper treatment than whatever we can get at from individual lines in individual stories. Weiss is right that the news business has the power to elevate people’s stories and voices; there may be a commitment to doing so in its coverage. We should encourage them to do the same in the boardroom.

在《紐約時報》上,我還沒有討論多樣性的另一個重要方面:生產和保存所寫故事的人的身份。 我認為,這與對地理表示法的任何關注一樣重要,并且需要比我們從單個故事中的單個臺詞所能得到的任何東西更深入的對待。 魏斯(Weiss)說的對,新聞業有能力提升人們的故事和聲音是正確的; 可能會承諾在其范圍內這樣做。 我們應該鼓勵他們在董事會做同樣的事情。

翻譯自: https://medium.com/swlh/the-shifting-definition-of-newsworthiness-1566c0430a14

自定義按鈕動態變化

本文來自互聯網用戶投稿,該文觀點僅代表作者本人,不代表本站立場。本站僅提供信息存儲空間服務,不擁有所有權,不承擔相關法律責任。 如若轉載,請注明出處:http://www.pswp.cn/news/389783.shtml 繁體地址,請注明出處:http://hk.pswp.cn/news/389783.shtml 英文地址,請注明出處:http://en.pswp.cn/news/389783.shtml

如若內容造成侵權/違法違規/事實不符,請聯系多彩編程網進行投訴反饋email:809451989@qq.com,一經查實,立即刪除!分析(轉載))