(Related post: On a scale from 1 to 10, how much do the numbers used in survey scales really matter?)

(相關文章: 從1到10的量表,調查量表中使用的數字到底有多重要? )

At Pew Research Center, survey questions about respondents’ political ideology are among the most important measures in our comparative, cross-national surveys. Our recent research in Europe, for instance, explored how political polarization in the region shapes long-standing debates about domestic, social and economic policies.

在皮尤研究中心,關于受訪者的政治思想的調查問題是我們的比較性跨國調查中最重要的指標之一。 例如,我們最近在歐洲進行的研究探討了該地區的政治兩極化如何形成有關國內,社會和經濟政策的長期爭論。

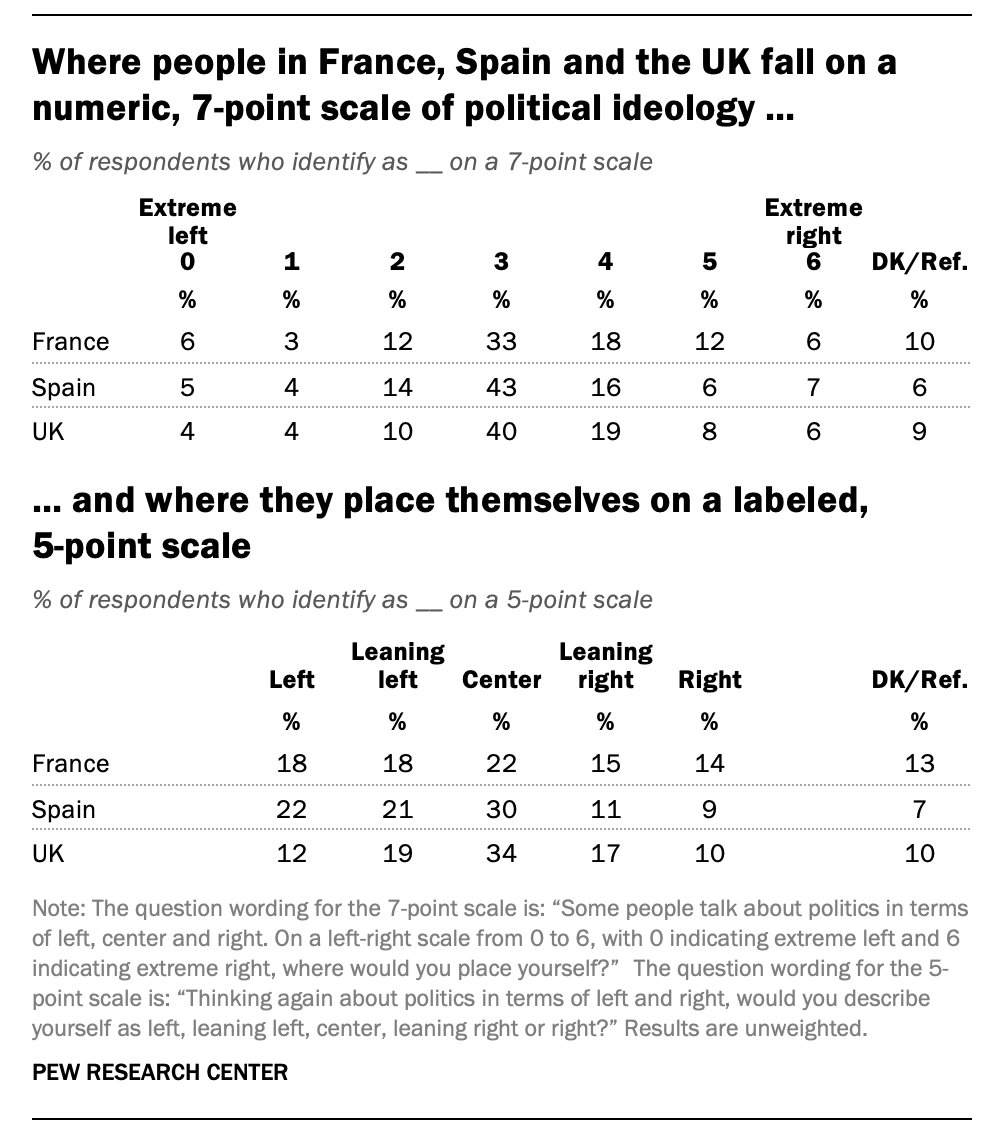

To measure political ideology, our international questionnaires typically ask respondents to place themselves on a 7-point scale with two labeled endpoints (or anchors) — “extreme left” and “extreme right” — along with numbers for all of the points in between. However, some research suggests that it’s easier for respondents to understand a fully labeled scale, one that includes descriptions for the interior points as well, such as “leaning left,” “leaning right,” or “center.” In this post, we’ll describe a survey experiment we conducted to find out if two approaches to measuring the same concept align with — or diverge from — each other.

為了衡量政治意識形態,我們的國際調查問卷通常要求受訪者將自己置于7點制范圍內,并帶有兩個標記的端點(或錨點)“極左”和“極右”,以及介于兩者之間的所有點的數字。 但是, 一些研究表明,受訪者更容易理解帶有完整標簽的量表,該量表還包含內部點的描述,例如“向左傾斜”,“向右傾斜”或“中心”。 在這篇文章中,我們將描述一個調查實驗,以發現兩種測量同一概念的方法是否相互兼容或相異。

發現一目了然 (Findings at a glance)

Our survey experiment was part of nationally representative telephone surveys we fielded in France, Spain and the United Kingdom in the spring of 2018. (You can read about an earlier experiment related to survey scales in this Decoded post.)

我們的調查實驗是我們于2018年Spring在法國,西班牙和英國進行的全國代表性電話調查的一部分。(您可以在此解碼后的帖子中了解有關調查規模的更早實驗。)

The 2018 surveys asked about political ideology in two ways. First, midway through each interview, respondents were asked the Center’s standard ideology question using a 7-point numeric response scale with only the endpoints labeled. Then, after several more questions, respondents were asked to describe themselves using a fully labeled, 5-point scale.

2018年的調查以兩種方式詢問政治意識形態。 首先,在每次面談的中途,使用7點數字回答量表(僅標出端點)向受訪者詢問中心的標準意識形態問題。 然后,在再問了幾個問題后,要求受訪者使用完全標記的5分制量表來描述自己。

Here are some of the trends we observed across all three countries:

以下是我們在所有三個國家/地區觀察到的一些趨勢:

· The most common response option for both scales was the midpoint, though a greater share of respondents chose the midpoint on the 7-point scale (“3”) than on the 5-point scale (“center”).

·兩種量表上最常見的回答選項是中點,盡管更多的受訪者選擇了7點量表(“ 3”)而不是5點量表(“中心”)。

· More respondents identified as right of center on the 7-point scale but left of center on the 5-point scale.

·更多的受訪者將其確定為以7分制為中心居中,但以5分制為中心居中。

· Respondents were more likely to choose the endpoints on the 5-point scale than on the 7-point scale, and this was especially true for those on the ideological left.

·受訪者更有可能選擇5點制的端點,而不是7點制的端點,對于意識形態左翼的人尤其如此。

· Levels of item nonresponse (either “don’t know” or refusal to answer) were similar using both approaches.

·使用兩種方法,項目無響應的級別(“不知道”或拒絕回答)相似。

使用Sankey圖仔細查看法國 (A closer look at France using Sankey diagrams)

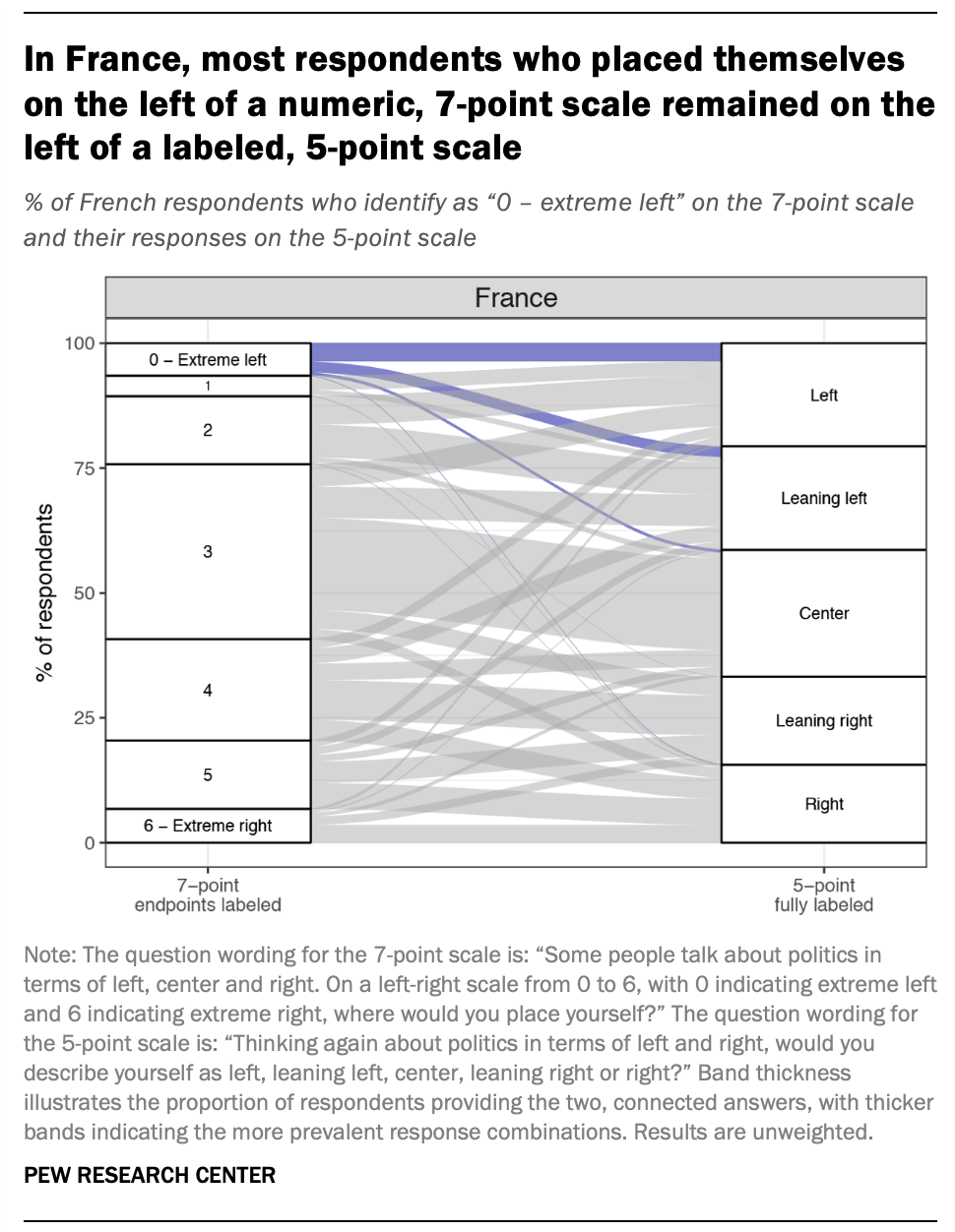

These aggregate numbers don’t tell the whole story. Fortunately, we can go a step further with our experimental data. By asking all respondents to answer both versions of our ideology question, we can also see how each respondent answered — or “moved” — from one question to the other.

這些總數并不能說明全部情況。 幸運的是,我們可以進一步利用實驗數據。 通過要求所有受訪者回答我們意識形態問題的兩個版本,我們還可以看到每個受訪者如何從一個問題回答另一個問題。

To illustrate these patterns, we created Sankey diagrams for each country using the R package ggalluvial. These graphs are a type of flow diagram that illustrate the movement from one category to the next — in this case, from the 7-point scale to the 5-point version. The band thickness in Sankey diagrams indicates the number of people taking a particular path, with thicker bands showing the more common pathways between two points on our different scales. (We should note at the outset that this part of our analysis does not include respondents who answered “don’t know” or refused to respond. It is limited to the 2,625 respondents who answered both ideology questions, including 846 in France, 935 in Spain and 844 in the UK.)

為了說明這些模式,我們使用R包ggalluvial為每個國家/地區創建了Sankey圖。 這些圖是一種流程圖,說明了從一個類別到下一個類別的移動-在這種情況下,是從7點刻度到5點刻度。 Sankey圖表中的條帶厚度表示沿著特定路徑行駛的人數,條帶越粗表示我們在不同尺度上的兩個點之間的路徑越常見。 (我們首先要注意的是,我們的這一部分分析不包括回答“不知道”或拒絕回答的受訪者。僅限于回答這兩個意識形態問題的2,625名受訪者,包括法國的846名,法國的935名。西班牙和英國的844。)

In the graph on the left, we’ll focus on French respondents who answered “0 — Extreme left” on the ideology question using the 7-point scale. Of the 55 French respondents who reported “0 — Extreme left,” most of them (31) chose “left” when later asked to identify their political ideology using the 5-point scale. These respondents are represented by the highlighted horizontal line straight across the top of the chart.

在左側的圖表中,我們將重點關注使用7分制在意識形態問題上回答“ 0-極左”的法國受訪者。 在55名法國受訪者中,他們將“ 0 –極左”表示為“左”,其中大多數(31)在后來被要求使用5分制來確定其政治思想時選擇了“左”。 這些受訪者均由突出顯示在圖表頂部的水平線表示。

But what about the 24 other people in France who chose the “0 — Extreme left” option? These respondents are represented by three narrower bands that start at “0 — Extreme left” and then slide down and to the right in the chart. Overall, most of these respondents (18) chose “leaning left.” Far fewer moved to “center” (five respondents) or “right” (one respondent). None of the respondents who answered “0 — Extreme left” on the 7-point scale reported “leaning right” on the 5-point scale.

但是,法國的其他24個人選擇了“ 0-極左”選項又如何呢? 這些受訪者由三個較窄的帶代表,從“ 0-極左”開始,然后在圖表中向下和向右滑動。 總體而言,這些受訪者中的大多數(18)選擇了“向左傾斜”。 轉移到“中心”(五個受訪者)或“正確”(一個受訪者)的人數更少。 在7分制中回答“ 0-極左”的受訪者中沒有一個在5分制中報告“向右傾斜”。

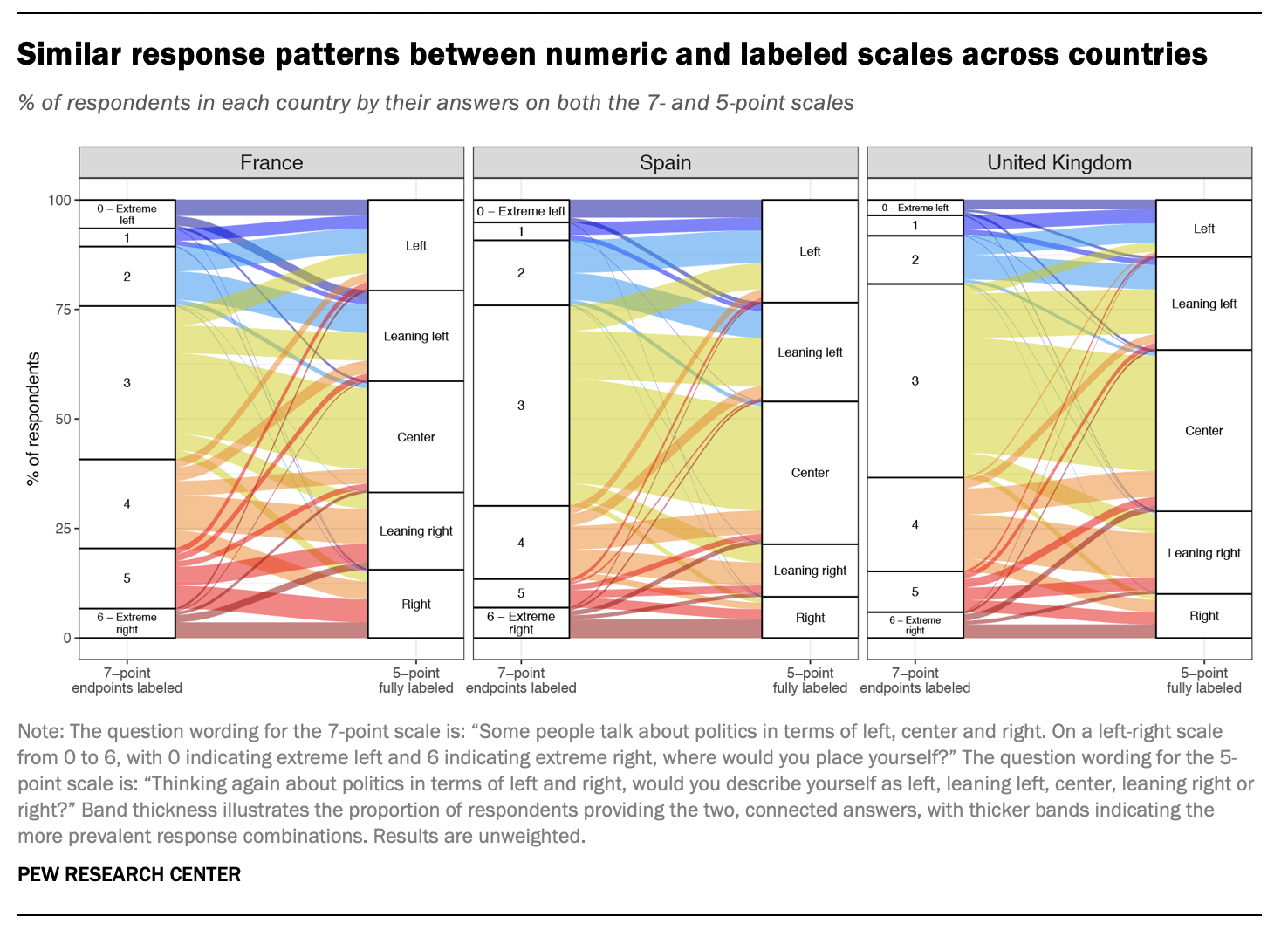

The full range of patterns between the two scales in France is provided in the next Sankey diagram, with the path of each combination of responses illustrated by a different color.

下一張Sankey圖中提供了法國兩個刻度之間的全部圖案范圍,每種響應組合的路徑都用不同的顏色表示。

A few trends emerge in this graph:

該圖顯示了一些趨勢:

· About half of the respondents (53%) who selected the midpoint on the 7-point scale also chose “center” on the 5-point scale, as illustrated by the thickest yellow band connecting “3” to “center.” Among those who chose the midpoint on the 7-point scale but did not choose “center” on the 5-point scale, roughly twice as many placed themselves left of center than right of center: 31% versus 17%.

·大約一半的受訪者(53%)選擇了7點制的中點,也選擇了5點制的“中心”,如將“ 3”連接到“中心”的最粗的黃色帶所示。 在選擇了7分制中點但未選擇5分制“中點”的人中,將自己置于中心點左側的比例是中心點右側的兩倍:31%對17%。

· Nine-in-ten (90%) of those on the left of the 7-point scale identified as left of center on the 5-point scale as well, as illustrated by nearly all of the blue bands above the midpoint moving to either “left” or “leaning left.” Overall, 7% of those who characterized their ideology as left of center on the 7-point scale moved to “center” on the 5-point scale, while 3% moved to “leaning right” or “right.”

·7點標尺左側的十分之九(90%)也在5點標尺上也標識為中心的左側,如中點上方的幾乎所有藍色帶向任一方向移動所示“向左”或“向左傾斜”。 總體上,在7點制中以意識形態為中心的人中有7%移至5點制中以“中心”為中心,而3%的人則以“向右傾斜”或“向右”移動。

· Around two-thirds of respondents (66%) who placed themselves on the right of the 7-point scale also chose “right” or “leaning right” on the 5-point scale. Surprisingly, more of those who identified as right of center on the 7-point scale identified as “left” or “leaning left” on the 5-point scale (21%) than moved to the center (13%). This is shown by the similarly sized orange and red paths heading to “left,” “leaning left,” and “center.”

·大約三分之二的受訪者(66%)將自己置于7分制的右邊,也選擇了5分制的“對”或“傾斜對”。 令人驚訝的是,在7分制中被標識為中心右的人在5分制中被標識為“左”或“向左傾斜”(21%),而不是移到中心(13%)。 朝著“左”,“向左傾斜”和“中心”的大小相似的橙色和紅色路徑顯示了這一點。

· Of the 35 possible response combinations between questions, no respondents in France answered “0 — Extreme left” on the 7-point scale and later identified as “leaning right” on the 5-point scale, or answered “1” and then identified as “center” or “leaning right.”

·在問題之間的35種可能的回答組合中,法國沒有受訪者在7分制中回答“ 0-極左”,后來在5分制中確定為“向右傾斜”,或者回答“ 1”,然后確定作為“中心”或“向右傾斜”。

實驗的跨國結果 (Cross-national results from the experiment)

Sankey diagrams can also be helpful to illustrate and better understand cross-national patterns in our three selected countries. As the next chart shows, several of the broad trends we observed in France are apparent in Spain and the UK as well:

Sankey圖還有助于說明和更好地理解我們三個選定國家中的跨國模式。 如下圖所示,我們在法國觀察到的一些廣泛趨勢在西班牙和英國也很明顯:

Here’s a closer look at what’s happening in this chart:

以下是此圖表中發生的情況的詳細信息:

· Across all three countries, most respondents who chose the midpoint on the 7-point scale also chose “center” on the 5-point scale (53% in France, 52% in Spain and 59% in the UK). And just as in France, more people moved from the midpoint of the 7-point scale to left of center on the 5-point scale than moved to the right on the 5-point scale.

·在這三個國家中,大多數選擇7分制中點的受訪者也選擇5分制“中點”(法國為53%,西班牙為52%,英國為59%)。 就像在法國一樣,從5點標度的7點標度的中點移動到5點標度的中心左側的人數多于5點標度的向右轉移的人數。

· In all three countries, the overwhelming majority of those who placed themselves on the left of the 7-point scale also identified as left of center on the 5-point scale (90% in France, 94% in Spain and 89% in the UK).

·在這三個國家/地區中,絕大多數將自己置于7分制左側的人也確定為5分制中央的左側(法國為90%,西班牙為94%,西班牙為89%英國)。

· There is more variability among those who placed themselves on the right of the 7-point scale. While 66% of those on the ideological right in France also placed themselves on the right of the 5-point scale, the share who did so was lower in both Spain (52%) and the UK (61%). Respondents on the ideological right of the 7-point scale in Spain and the UK were more likely than their counterparts in France to move to the center on the 5-point scale (26% in Spain and 25% in the UK versus 13% in France).

·將自己置于7分制右邊的人之間的差異更大。 盡管法國有66%的意識形態權利人也將自己置于5分制的權利,但西班牙(52%)和英國(61%)的比例均較低。 在西班牙和英國的7分制的思想右被訪者認為自己在法國的同行更容易移動到西班牙在英國的5分制中心 (26%和25%比13%法國)。

· As was the case in France, a few combinations of responses were not found in Spain and the UK. No respondents in Spain answered “0 — Extreme left” and then “center” or “leaning right,” or, in another combination, “1” and then a right-of-center response. Similarly, in the UK, no respondents first answered “0 — Extreme left” or “1” and then “right.”

·與法國一樣,西班牙和英國未發現一些回應組合。 西班牙沒有受訪者回答“ 0-極端偏左”,然后回答“居中”或“向右傾斜”,或者回答“ 1”再回答居中偏右。 同樣,在英國,沒有受訪者首先回答“ 0-極端左”或“ 1”,然后回答“右”。

As illustrated in the Sankey diagrams, there is general ideological consistency at the individual respondent level between the two survey questions, with only a limited share of people in each country providing apparently contradictory answers. In fact, only 11 of our 2,625 respondents provided the opposite extremes to the two scales (“0-Extreme left” and right or “6-Extreme right” and left). The robustness of these measures across countries suggests that both items can be useful in estimating political ideology. Across countries, our respondents behaved similarly, but not exactly the same. This is reflected in the subtle variability in responses to these two questions that are seemingly measuring the same thing.

如桑基圖所示,在兩個調查問題之間,每個受訪者在思想層面上都具有普遍的一致性,每個國家中只有有限的一部分人提供明顯矛盾的答案。 實際上,在我們的2,625名受訪者中,只有11個對兩個量表(“ 0極左”和右或“ 6極右”和左 )給出了相反的極端。 各國這些措施的健全性表明,這兩個項目都可用于估計政治意識形態。 在各個國家/地區,我們的受訪者的行為相似,但并不完全相同。 這似乎反映了對似乎正在衡量同一事物的這兩個問題的回答的細微差異。

結論性思想 (Concluding thoughts)

Both scales have benefits. A 5-point, fully labeled scale allows respondents to identify with a qualitative description of their political leaning, while a 7-point, endpoint labeled scale provides respondents with more choices to select a position closest to their political ideology. While the two survey questions are different in scale size and wording, respondents across countries answered them in similar patterns, giving us confidence in both when conducting cross-country comparisons.

兩種規模都有好處。 5點,完全標記的量表使受訪者能夠定性地描述其政治傾向,而7點,最終標記的量表則為受訪者提供了更多選擇來選擇最接近其政治意識形態的職位。 雖然這兩個調查問題的規模和措詞不同,但各國的受訪者以相似的方式回答了這些問題,這使我們對進行跨國比較時的兩個問題充滿信心。

There are several caveats, however. The experiment relied on relatively small samples that limited our findings in a few ways. For example, we could not conduct robust analyses across all possible answer combinations because some were too infrequent and others nonexistent. And while some respondents answered with “don’t know” or refused to answer at all, the number of people who did so was relatively small, limiting our ability to draw inferences about this group.

但是,有幾個警告。 實驗依靠相對較小的樣本,這些樣本在某些方面限制了我們的發現。 例如,我們無法對所有可能的答案組合進行可靠的分析,因為其中一些頻率太低而另一些頻率不高。 盡管有些受訪者回答“不知道”或根本拒絕回答,但這樣做的人數相對較少,這限制了我們對這一群體進行推斷的能力。

Aside from sample size, there are a few other issues we would consider expanding upon in future experiments. For instance, we did not rotate question order to examine whether replying to the first ideology question affected respondents’ answers to the second question or subsequent items. Also, we tested only two response scales, which means we could not assess the merits of other permutations, such as the results of a fully labeled, 7-point scale or a numeric, endpoint-labeled 5-point scale.

除了樣本數量外,我們還將考慮在以后的實驗中擴展其他一些問題。 例如,我們沒有輪換問題順序來檢查對第一個意識形態問題的答復是否影響了受訪者對第二個問題或后續項目的回答。 此外,我們僅測試了兩個響應量表,這意味著我們無法評估其他排列的優劣,例如完全標記的7點量表或數字的端點標記的5點量表的結果。

Finally, the questions we tested weren’t equivalent. The Center’s standard political ideology question includes the words “extreme” (in the 7-point scale itself) and “center” (in the question stem), but this is not the case in the alternative 5-point scale and associated question. Additional experimental conditions — say, keeping the scale length the same but testing different wordings, or vice versa — would allow us to disentangle these effects.

最后,我們測試的問題并不相同。 中心的標準政治意識形態問題包括“極端”(在7點量表本身中)和“中心”(在問題詞干中)兩個詞,但在另選5點量表和相關問題中則不是這種情況。 額外的實驗條件(例如,保持標尺長度相同,但測試不同的措詞,反之亦然)將使我們能夠解開這些影響。

To dig deeper, it might be useful to look beyond the survey results. It’s possible some respondents were confused when we asked for their political ideology twice, so one way to explore the issue would be to incorporate cognitive interviewing in future experiments. This may help researchers better understand the meaning of survey questions, including questions that ask about the same underlying concept, from a respondent’s point of view.

要進行更深入的研究,可能需要超越調查結果。 當我們兩次詢問他們的政治意識形態時,有些受訪者可能會感到困惑,因此探討該問題的一種方法是將認知訪談納入未來的實驗中。 這可能有助于研究人員從受訪者的角度更好地理解調查問題的含義,包括詢問相同基礎概念的問題。

In the meantime, we plan to use the data from this experiment to further study whether one of these ideology questions is a more accurate or valid measure than the other. Comparing each question with other items asked in our surveys — such as respondents’ political party affiliation or their opinions on highly politicized topics — would provide additional insights, with the help of Sankey diagrams to visualize the results.

同時,我們計劃使用該實驗中的數據進一步研究這些意識形態問題中的一個是否比另一個更準確或更有效。 將每個問題與我們調查中詢問的其他項目(例如,受訪者的政黨隸屬關系或他們對高度政治化的話題的看法)進行比較,將借助Sankey圖表將結果可視化,從而提供更多的見解。

This post was written by Martha McRoy and Stacy Pancratz. Both are research methodologists focusing on international survey research methods at Pew Research Center.

該帖子由Martha McRoy和Stacy Pancratz撰寫。 兩位都是皮尤研究中心專注于國際調查研究方法的研究方法學家。

翻譯自: https://medium.com/pew-research-center-decoded/small-changes-in-survey-scales-can-matter-when-measuring-political-ideology-in-europe-4a10d9a015c5

本文來自互聯網用戶投稿,該文觀點僅代表作者本人,不代表本站立場。本站僅提供信息存儲空間服務,不擁有所有權,不承擔相關法律責任。 如若轉載,請注明出處:http://www.pswp.cn/news/389583.shtml 繁體地址,請注明出處:http://hk.pswp.cn/news/389583.shtml 英文地址,請注明出處:http://en.pswp.cn/news/389583.shtml

如若內容造成侵權/違法違規/事實不符,請聯系多彩編程網進行投訴反饋email:809451989@qq.com,一經查實,立即刪除!

方法源碼解析(二))

)

python在anaconda安裝opencv庫及skimage庫(scikit_image庫)諸多問題解決辦法)

)