數據可視化 信息可視化

Data visualization is a great way to celebrate our favorite pieces of art as well as reveal connections and ideas that were previously invisible. More importantly, it’s a fun way to connect things we love — visualizing data and kicking up our feet for a movie night. All week, Nightingale is exploring the intersections between data visualization and all kinds of entertainment.

數據可視化是慶祝我們最喜歡的藝術品以及揭示以前不可見的聯系和想法的好方法。 更重要的是,這是連接我們喜歡的事物的一種有趣方式-可視化數據并為電影之夜踢起腳來。 整個晚上,夜鶯都在探索 數據可視化與各種娛樂之間 的 交集 。

From the sensational Tiger King, to the meme-inspiring Ancient Aliens, to the hypnotic Blue Planet, to the [cathartically?] disastrous Fyre, documentaries are a mainstream, pop-culture vehicle for “truth-telling” and nonfiction storytelling.

f光盤煽情虎王 ,為“講真話”和非小說評書梅梅,鼓舞人心的遠古外星人 ,到催眠藍色星球 ,到[cathartically?]災難性Fyre,紀錄片是一個主流,流行文化的載體。

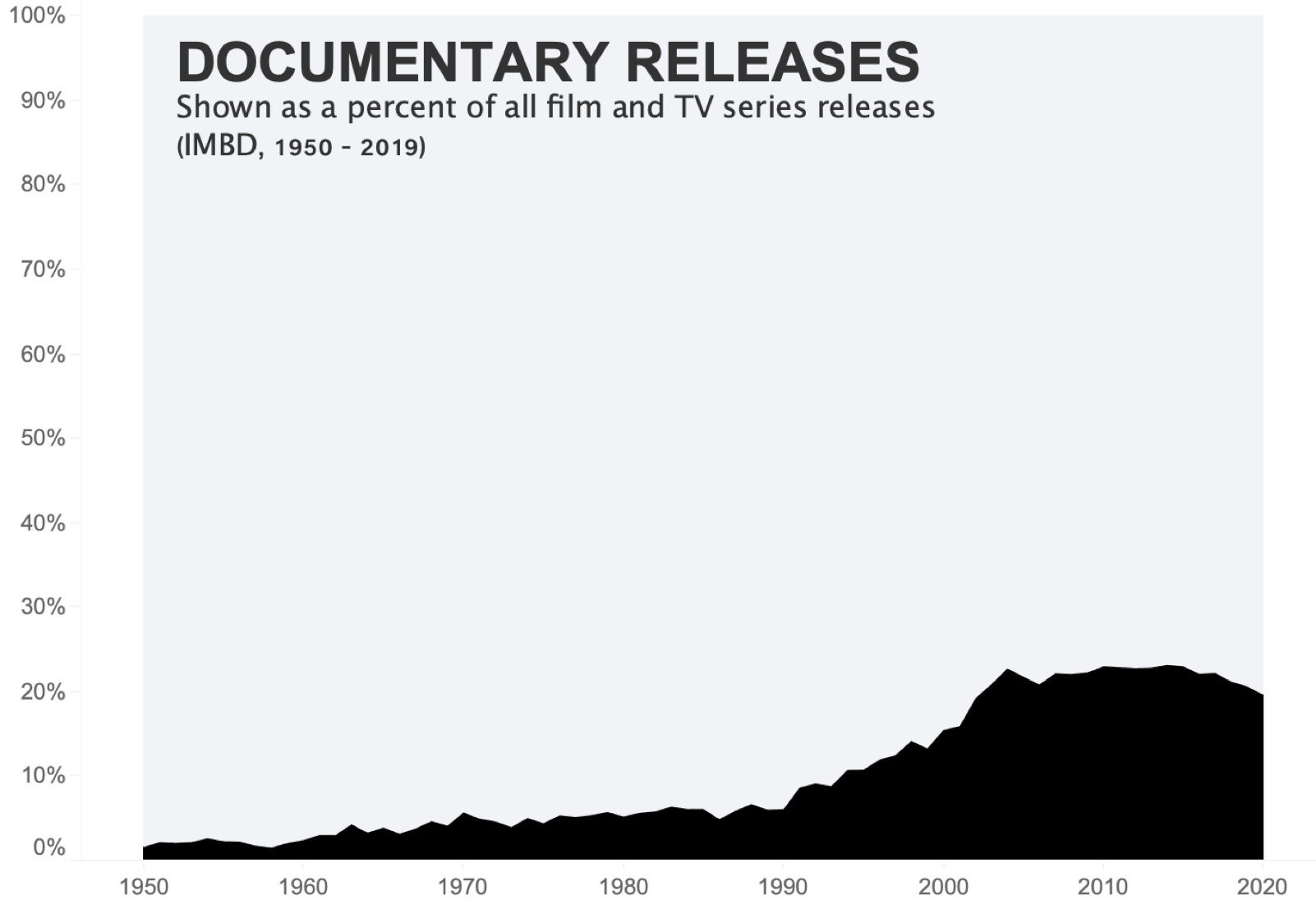

Anecdotally, it feels like lately I’m more likely to be recommended a documentary on a topic versus a book or even a podcast. Not only are they doing increasingly well at the box office, documentaries have increasingly captured more of the share of content we consume from the big screen — from less than 2% of all films and TV series 50 years ago to 20% last year.

有趣的是,最近覺得我更有可能被推薦為關于主題的紀錄片,而不是書甚至是播客。 他們不僅在票房上表現越來越好,而且紀錄片也越來越多地捕獲了我們從大屏幕上消費的內容份額–從50年前所有電影和電視連續劇中的不到2%到去年的20%。

Documentaries are the natural byproduct of our love of motion picture storytelling expressed during the information age. Documentary producer Dan Cogan, whose company has produced or funded over a hundred documentaries, said, “We are in the Golden Age of documentary film making. … There has never been as great storytelling in nonfiction film as there is today.”

紀錄片是我們在信息時代表達對電影故事的熱愛的自然副產品。 紀錄片制作人丹·科根(Dan Cogan)制作或資助了一百多部紀錄片, 他說 :“我們正處于紀錄片制作的黃金時代。 ……在非虛構電影中,從來沒有像今天這樣偉大的故事講述。”

We get to learn while enjoying all the things we love about fiction narratives: edge-of-our-seat intrigue, obsession over mystery, teary-eyed redemption arcs, comedic tragedies.

我們在學習的同時享受著關于小說敘事的所有熱愛:我們的邊緣陰謀,對神秘的迷戀,眼淚的救贖弧,喜劇悲劇。

What a wonderful time to learn.

多么美好的學習時間。

While I’d love to wax poetic on documentary narratives, this piece is really about the similarity to data storytelling: both arts are informing via narrative.

盡管我很想在紀錄片敘事上增添詩意,但這篇文章實際上是關于數據敘事的相似之處:兩種藝術都通過敘事來傳達信息。

Given the rising interest in documentary as a medium that so artfully marries learning and story, it makes sense that similar demands would fall on the “data” world. Our users and audiences aren’t satisfied with facts—they desire entertainment, exposition, intrigue.

鑒于人們對紀錄片作為一種巧妙地結合學習和故事的媒體的興趣日益濃厚,因此類似的需求將落在“數據”世界上是有道理的。 我們的用戶和觀眾對事實不滿意-他們渴望娛樂,展示和陰謀。

We crave the form of meaning that only stories can deliver. It’s not enough to know something, we want to experience it through the perspective of a narrator and characters.

我們渴望只有故事才能傳達的意義形式。 僅僅了解某件事是不夠的,我們希望通過敘述者和角色的視角來體驗它。

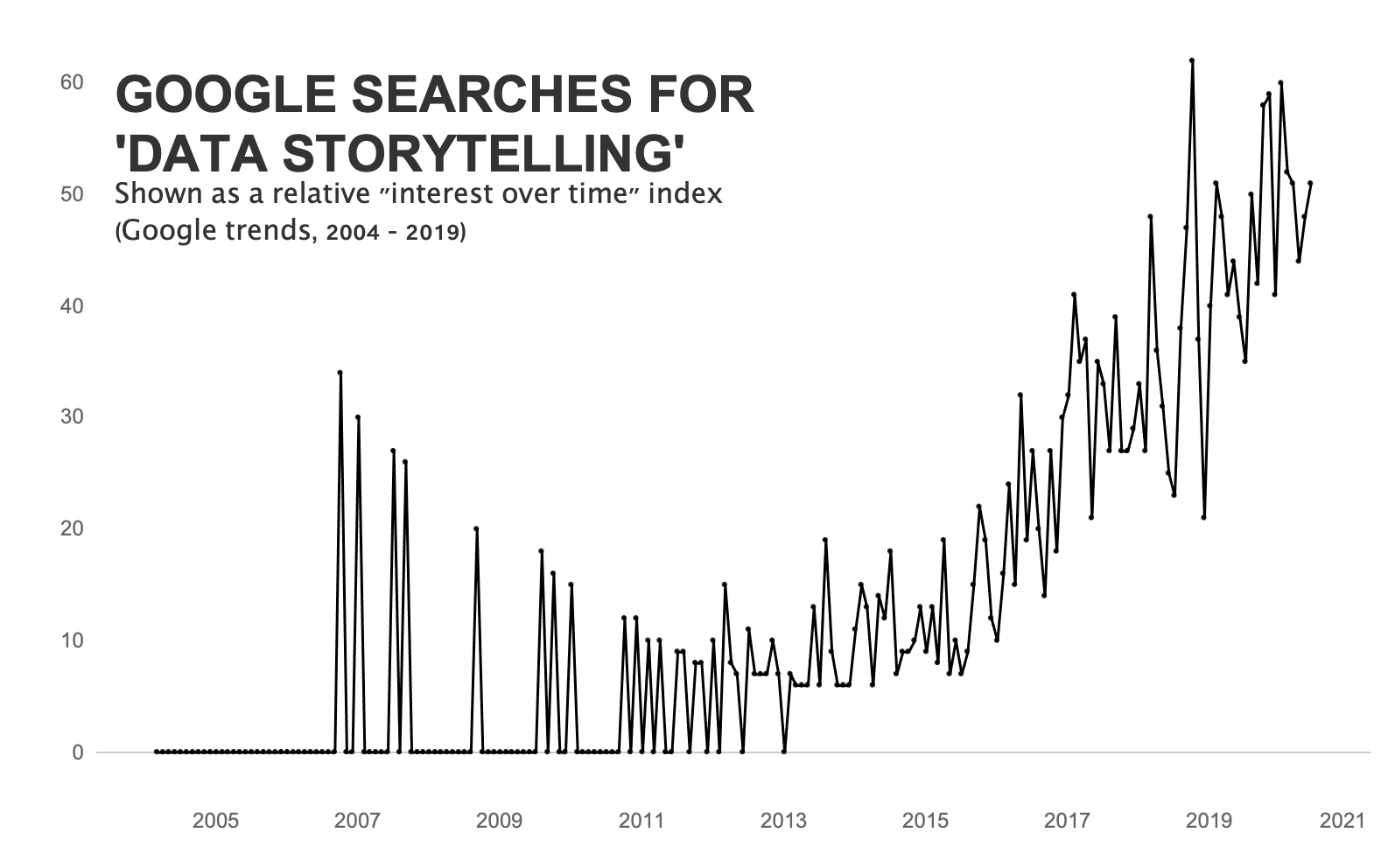

Along with the rise of documentaries, we can follow the rise of “data storytelling.” Since 2011, Google searches for the phrase “data storytelling” have dramatically increased (with a noteworthy acceleration in 2015 after Cole Nussbaumer Knaflic published her discipline-defining title, Storytelling with Data).

隨著紀錄片的興起,我們可以追隨“數據故事講述”的興起。 2011年以來,谷歌搜索短語“數據說話”有大幅提升(與科爾NUSSBAUMER Knaflic后,在2015年一個值得注意的加速出版了她的紀律定義標題, 講故事用數據 )。

What might have once been a buzzword is now codified into a sought-out skill set. Nussbaumer’s book was followed by this book and this book and this book and this book and this book and this book and this book and this book and I’m sure others that aren’t waving their hands at the top of Amazon’s search algorithm. Storytelling, UX, and information design was a track at this year’s DataVizLive conference. It’s long been a criteria for judging in Tableau Conference’s IronViz competition.

曾經曾經是一個流行語的東西現在被編入了一個備受追捧的技能組。 緊接著Nussbaumer的書, 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書 , 這本書以及這本書 ,我敢肯定,其他人不會在Amazon搜索算法的頂部揮舞自己的雙手。 講故事,用戶體驗和信息設計是今年DataVizLive會議的主題。 長期以來,Tableau Conference的IronViz競賽一直是評判標準。

Data storytelling isn’t a trendy buzzword, it’s a preference in how we consume information and how we learn.

數據講故事并不是一個時髦的流行語,它是我們如何消費信息和學習方式的首選。

Don’t give me a chart—give me a story.

不要給我一張圖表,而是給我一個故事。

So we’ve seen a parallel in the rise of the documentary and data storytelling, both crafts that pair information with narrative, insights with entertainment.

因此,我們看到了紀錄片和數據講故事的興起,兩者都將信息與敘事,洞察力與娛樂結合在一起。

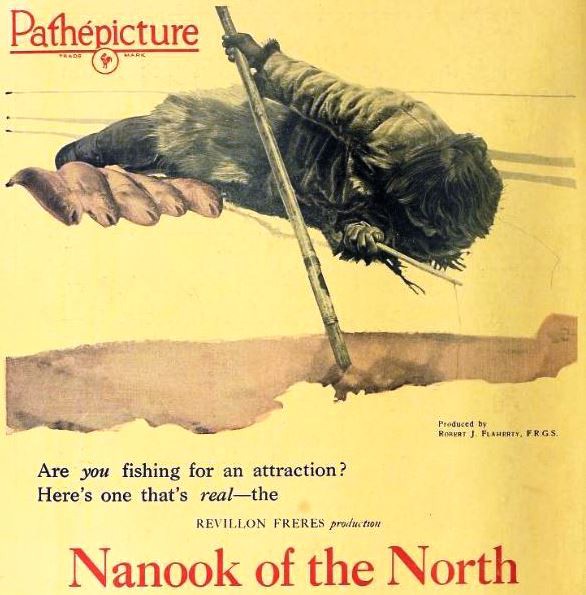

Although both crafts are currently very prevalent, documentaries have been at this game for a lot longer. While identifying the “first” documentary requires navigating some academic arguments on genre, the consensus is that the ethnographic Nanook of the North, by Robert Flaherty, was the first—in 1922.

盡管目前兩種Craft.io都很流行,但紀錄片在這場比賽中已經存在了很長時間。 同時確定了“第一”的紀錄片,需要導航流派一些學術爭論,共識是,人種學北方的納努克 ,由羅伯特·弗萊厄蒂,是先于1922年。

Fast forward nearly a century: Nussbaumer’s groundbreaking book Storytelling with Data came out in 2015. Of course people were pairing narratives with data before that book, but it feels pretty clear that as a practiced and disciplined craft, documentaries are our elder.

快進近一個世紀:努斯鮑姆(Nussbaumer)開創性的書《講故事與數據》于2015年問世。當然,人們在那本書之前將敘述與數據配對,但很顯然,紀錄片是我們的老練紀律。

And, just as our elders can say “Oh, I’ve solved that before, just try this,” documentaries can show us a number of techniques we can use to marry information and narratives.

而且,就像我們的長輩可以說:“哦,以前我已經解決了,只需嘗試一下即可。 ”紀錄片可以向我們展示許多可用于結合信息和敘述的技術。

中立的神話 (The myth of neutrality)

Documentaries—especially observational documentaries—create a sense of truth about what we’re seeing, especially when the film crew are “invisible.” This isn’t just true of documentaries, it’s true of a lot of video.

紀錄片,尤其是觀察片 紀錄片-使我們對所看到的事物有一種真實感,尤其是當攝制組是“隱形的”時。 這不僅適用于紀錄片,還適用于許多視頻。

However, filmmaker choice guides what we see. Editing determines the order in which we see things and what we don’t see. Things like music and filmography impact the value we place on what we’re seeing (for example, the same interaction between two people could be perceived as positive or negative, depending on the background music).

但是,制片人的選擇將指導我們所看到的。 編輯決定了我們看到事物的順序和看不到事物的順序。 諸如音樂和電影攝影之類的事物會影響我們對所看到事物的重視(例如,取決于背景音樂,兩個人之間相同的互動可能會被感知為正面或負面)。

On the more malicious end, Nanook of the North intentionally staged the narrative to portray the Inuits in a negative and subhuman light. Much of what we saw of the protagonist, Nanook (whose actual name was Allakariallak), is distorted or fabricated. Many of Flaherty’s directorial decisions played into colonial voyeurism, forcing real people to fit into a Euro-American narrative of Indigenous people.

在更為惡意的方面, 北方的納諾克(Nanook)故意上演了敘事,以消極的,不合人類的眼光描繪了因紐特人 。 我們看到的主角Nanook(實際上的名字是Allakariallak)的大部分內容都是失真的或虛構的。 弗萊厄蒂(Flaherty)的許多導演決定都導致了殖民窺淫癖,迫使真實的人融入了歐美人對土著人的敘述中。

Yet providing an “unbiased” recording of reality isn’t possible (this isn’t to justify Flaherty’s colonialist narrative—our biases can certainly be intentional and malicious). In the literary version of social science’s Observer Effect, simply bringing a camera into an environment changes the behavior of the subject being filmed. In addition, some environments can’t be filmed as they are, and so observing “truth” may require modifying the environment. Nanook of the North provides another example here, as the filmmakers rebuilt the igloo as a three-walled structure to accommodate the large cameras. Giving viewers a glimpse of the living conditions inside an igloo required modifying the igloo itself.

但是,不可能提供“無偏見”的現實記錄(這不能證明弗萊厄蒂的殖民主義敘述是正當的-我們的偏見肯定是故意的和惡意的)。 在社會科學的《 觀察者效應》的文學版本中,僅將相機帶入環境即可改變被攝對??象的行為。 此外,某些環境無法照原樣拍攝,因此觀察“真實”可能需要修改環境。 北方的納諾克(Nanook)在這里提供了另一個例子,電影制片人將冰屋重建為三層結構,以容納大型相機 。 要讓觀眾瞥見冰屋內部的生活條件,就需要修改冰屋本身。

Much of this holds true for data storytelling. As analysts, we navigate similar decisions as documentary filmmakers. Filmmakers choose what to observe, we choose what data to analyze. Filmmakers choose their camera lens, we choose our analytic technique. Filmmakers edit out material and rearrange sequences, we choose which data to filter out and the ordering of our insights. Filmmakers choose music, images, fonts—so do we.

對于數據講故事,這大部分適用。 作為分析師,我們與紀錄片制片人一樣會做出類似的決定。 電影制片人選擇觀察的內容,我們選擇分析的數據。 電影攝制者選擇他們的相機鏡頭,我們選擇分析技術。 電影制片人剪輯出材料并重新排列序列,我們選擇要過濾的數據以及洞察力的順序。 電影制片人選擇音樂,圖像,字體,我們也是。

As analysts, we have to admit that we rebuild igloos, too.

作為分析師,我們必須承認我們也重建了冰屋。

There’s no such thing as a neutral documentary, and there’s no such thing as a neutral data story. Documentaries have been thinking about this far longer than we have, and it seems like perhaps a critical first question we can bring to the wisdom of our elder craft.

沒有中立的紀錄片,也沒有中立的數據故事。 紀錄片思考這個問題的時間比我們思考的時間長得多 ,似乎我們可以將這個古老Craft.io的智慧帶入一個至關重要的第一個問題。

旁白和旁白 (Voice-overs and narration)

One of my biggest turn-offs in data storytelling are walls of text. Like a real wall, a large body of text can prevent your audience from accessing your message, especially when used up-front. I find myself skimming the first few lines, then either skipping the rest or just closing the page altogether. Here’s one of the worst examples, from my own portfolio:

文字敘事是我最大的數據敘事之一 。 就像一堵真實的墻一樣,大量的文字可能會阻止聽眾訪問您的消息,尤其是在預先使用時。 我發現自己瀏覽了前幾行,然后跳過了其余幾行,或者只是完全關閉了頁面。 這是我自己的投資組合中最糟糕的例子之一:

Meanwhile, just this past weekend I was watching a documentary. About two minutes in, I found myself bored and distracted as a narrator paced around a set, rambling through a tedious exposition. I turned the documentary off.

同時,就在過去的一個周末,我正在觀看紀錄片。 大約兩分鐘后,我發現自己感到無聊和分心,因為一個解說員在一個布景中徘徊,漫步在一個乏味的展覽中。 我關閉了紀錄片。

Instead I turned on Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey. From the moment the studio logo disappeared, I was greeted with stunning images of beautiful landscapes, paired with a tribute Carl Sagan quote. The camera zoomed in to that landscape to find the narrator, Neil deGrasse Tyson, who provided me with a 14-second introductory exposition packed with intrigue and mystery. I was hooked as Tyson’s voice-overs elegantly explained the wondrous high-definition images I witnessed.

相反,我打開了《 宇宙:時空漫游》 。 從工作室徽標消失的那一刻起,我就被美麗的風景令人驚嘆的圖像所吸引,并向卡爾·薩根致敬。 相機放大到那個風景,找到了敘述者尼爾·德格拉斯·泰森(Neil deGrasse Tyson),他為我提供了14秒鐘的介紹性展覽,內容豐富且充滿神秘感。 泰森(Tyson)的畫外音優雅地解釋了我所看到的奇妙的高清圖像,這讓我著迷了。

演示地址

For a similar mastery in data storytelling, we can look to the Guardian’s 2017 “Bussed Out,” an award-winning data journalism piece about homelessness in the U.S. Journalism is a medium that typically relies on text, but from the get-go, “Bussed Out” integrates the exposition with images and animated data visualizations.

對于數據敘事的類似掌握,我們可以看一下《衛報》(Guardian)2017年的“ Bussed Out ”,這是屢獲殊榮的數據新聞行業的一篇有關美國無家可歸者的文章,該媒體通常依賴于文本,但從一開始就“瘋了” 將博覽會與圖像和動畫數據可視化集成在一起。

This piece really captures the essence of masterful narration as the charts fill out while I scroll through the story of individuals and society. Words live with charts, rather than just above, below, and beside them. Any lengthy bodies of text are accompanied with formatted quotes and plenty of negative space, creating openings in what might otherwise feel like walls.

當我滾動瀏覽個人和社會的故事時,這些圖表確實充滿了精湛敘事的精髓。 單詞與圖表一起生活,而不是僅僅在圖表的上方,下方和旁邊。 任何冗長的文本內容都帶有帶格式的引號和大量的負空格,從而在原本感覺像墻壁的地方創造了開Kong。

Too often I feel as if I’m given an instruction manual for a chart: Here’s what it shows, read it like this. “Bussed Out,” on the other hand, narrates my experience, seamlessly weaving evidence and explanation. We want to avoid being a tedious narrator, instead weaving visual voice-overs into our evidence.

我常常覺得好像給了我一張圖表的使用說明書: 這是它顯示的內容,像這樣閱讀 。 “花光了,” 另一方面,講述我的經歷,無縫地編織證據和解釋。 我們希望避免成為一個乏味的敘述者,而將視覺配音編織到我們的證據中。

面試 (Interviews)

I recently checked out the Netflix reboot of Unsolved Mysteries. I nostalgically remember Robert Stack’s distinctive voice as he narrated the mystery from foggy alleys, dark churches, cemeteries, or staged dispatch centers. The new Unsolved Mysteries, though, lacks a narrator. Instead, interviews are spliced together, feeding us clues and emotions like a carefully calculated multiple course meal, each preparing us for the next. The trailer, also lacking a narrator, showcases their interviewing technique:

我最近檢查了Netflix重新啟動的“ 未解之謎” 。 我懷舊地記得羅伯特·斯塔克獨特的聲音,他講述了在有霧的小巷,黑暗的教堂,墓地或上演的調度中心的奧秘 。 但是,新的《 未解之謎》沒有敘述者。 取而代之的是,采訪被拼接在一起,為我們提供了線索和情感,就像經過精心計算的多道菜一樣,每一次都使我們為下一次做準備。 預告片也缺少解說員,展示了他們的采訪技巧:

演示地址

The difference is compelling: Whereas the original Unsolved Mysteries were intriguing and suspenseful, I found this reboot to be tragic and sad as I felt hints of the loss of the friends and family being interviewed. In the original Unsolved Mysteries, the narrator was a mediator, protecting me from the tragedy by turning it into suspense. When the narration comes directly from the friends and family, I feel much closer to the story—and the raw emotion that comes with it.

兩者之間的差異令人信服:盡管原始的未解之謎令人著迷且令人生疑,但我發現這種重新啟動是悲劇性的和悲傷的,因為我感到被采訪的親朋好友流連忘返。 在最初的《 未解之謎》中 ,敘述者是調解人,通過將其變成懸念來保護我免受悲劇的侵害。 當敘述直接來自朋友和家人時,我會更接近這個故事以及隨之而來的原始情感。

Lisa Charlotte Rost discussed the inverse relationship between aggregation and empathy in her 2017 Open Viz presentation, A Data Point Walks Into a Bar: Designing Data for Empathy. It’s just easier to empathize with individuals we can see or hear.

麗莎·夏洛特·羅斯特(Lisa Charlotte Rost)在她的2017年Open Viz演講`` 數據點走進酒吧:為同理心設計數據''中討論了聚合與同理心之間的逆向關系。 同理心更容易 與個人 ,我們可以看到或聽到。

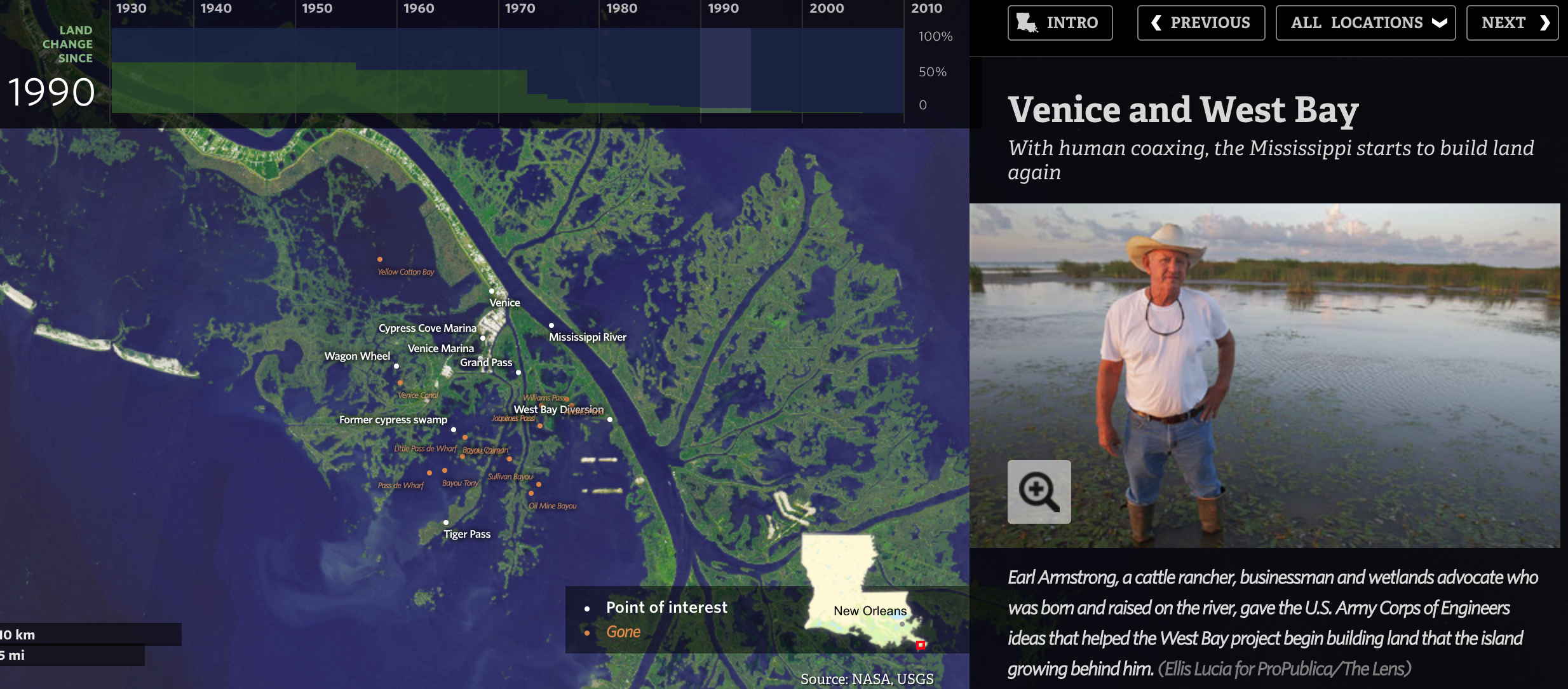

To that effect, I can still remember the first time I saw interviews paired with a data story: ProPublica’s “Losing Ground.” I stumbled across this in 2014, and I can still recall the powerful photograph of Earl Armstrong, a cattle rancher, standing in his field under a foot of water.

為此,我仍然記得我第一次看到采訪與數據故事相結合的情況: ProPublica的“ 失地 ” 。 我在2014年偶然發現了這一點,至今仍能回想起牛Rancher伯爵阿姆斯特朗(Earl Armstrong)站在水底下的強大照片。

I can remember the sound of his voice from the short recording. Granted, I’ve returned to this image over and over—but that’s because of the powerful way ProPublica paired aggregated data with individual interviews. Leading up to my discovery of “Losing Ground” I had seen my share of charts and data stories about climate change and rising coastal waters, but this was the first one that really stuck in my mind.

我可以從簡短的錄音中記住他的聲音。 誠然,我已經一遍又一遍地返回到該圖像,但這是因為 ProPublica將匯總數據與個人訪談配對的強大方式。 導致我發現“失落的土地” 我看到了有關氣候變化和沿海水域上升的圖表和數據故事,但這是我真正想到的第一個。

Both Unsolved Mysteries and ProPublica let people tell their own story. Whenever possible, they get out from between the subjects and the audience. All too often we think of data storytelling and data humanization as “telling the stories of the people in our data,” but I’d argue that we should look for opportunities let people tell their own story, rather than assume we have the power and right to speak on their behalf. We won’t always have that opportunity, but I think it’s a powerful device we should at least try to employ.

未解之謎和ProPublica都可以讓人們講述自己的故事。 只要有可能,他們就會從主題和聽眾之間脫身。 我們常常認為數據敘事和數據人性化是“在數據中講述人們的故事”,但我認為我們應該尋找機會讓人們講述自己的故事,而不是假設我們擁有力量和力量。代表他們發言的權利。 我們不會總是有這個機會,但是我認為這是我們至少應該嘗試使用的強大工具。

重演 (Reenactments)

I’m a big fan of the show River Monsters — it blends my hobby of fishing with my interest in folkoristics, all tossed together with a level of excitement. The host and angler, Jeremy Wade, chases down marine monsters by following stories of bizarre and often dangerous encounters. The show alternates between interviewing and reenacting the story they are telling. For some examples, watch some of the video below (content warning: mildly graphic descriptions and images of injury and death):

我是節目《 河怪獸》的忠實擁護者,它融合了我的釣魚愛好和對民俗學的興趣,所有這些都使人興奮不已。 主持人和垂釣者杰里米·韋德(Jeremy Wade)跟隨奇異且經常危險的相遇故事追逐海洋怪物。 該節目在采訪和重演他們講的故事之間交替進行。 例如,請觀看下面的一些視頻(內容警告:輕微的圖形描述以及受傷和死亡的圖像):

演示地址

Forensic Files, Unsolved Mysteries, and quite a few SyFy channel mystery shows employ this technique. Of course, it helps to inject suspense into the show—but it also provides educational value to help us understand the progression of events. Often reenactments are paired with step-by-step narratives to help our imaginations materialize the story: First this happened like this, then that happened like that, and so on.

法證文件 , 未解之謎和許多SyFy頻道的謎題節目都采用了這種技術。 當然,它有助于在節目中注入懸念,但是它也提供了教育價值,可以幫助我們了解事件的進展。 通常,重演與分步敘述相結合,以幫助我們的想象力實現故事: 首先是這樣的事情發生 , 然后是那樣的事情發生,依此類推。

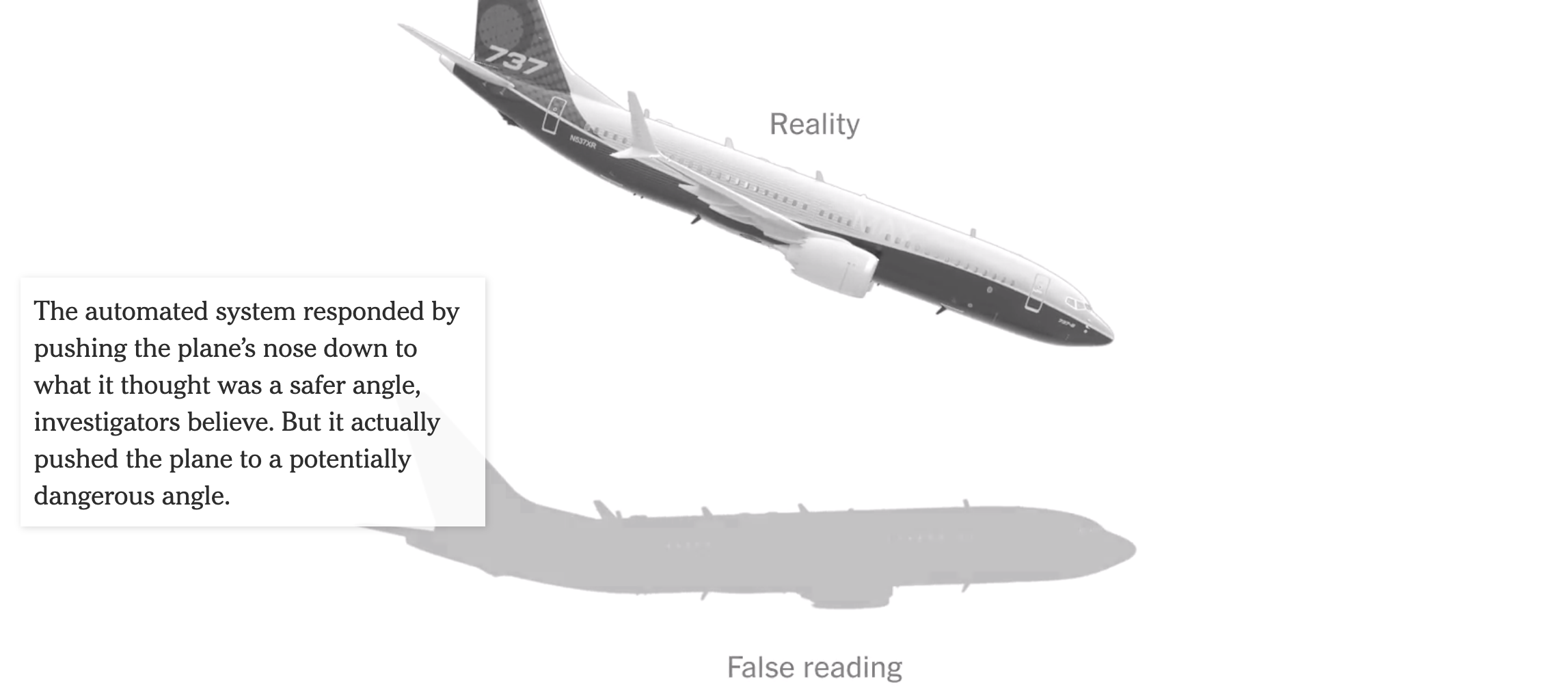

Perhaps the most obvious parallel between reenactments in documentaries and data viz is seen in animations. A strong example comes from NYT’s “The Dangerous Flaws in Boeing’s Automated System.” This piece brilliantly combines relatively simple graphics with scrolling annotations, narrating the plane’s angle of flight so the reader can follow exactly how faulty sensors may have caused a crash. We see how sensors are supposed to work, we see the safe angles for flight and we’re given a vocabulary. Then, the animations show us what happens when a sensor provides a false reading, and the diagram makes the potential danger very clear:

動畫中可以看到紀錄片中的重演與數據之間最明顯的相似之處。 紐約時報的“ 波音自動系統中的危險缺陷 ”就是一個很好的例子。 這篇文章巧妙地將相對簡單的圖形與滾動注釋結合在一起,講述了飛機的飛行角度,使讀者可以準確地了解有問題的傳感器可能導致墜機的原因。 我們看到了傳??感器應該如何工作,看到了飛行的安全角度,并且獲得了詞匯。 然后,動畫向我們展示了當傳感器提供錯誤讀數時會發生什么,該圖使潛在危險非常清楚:

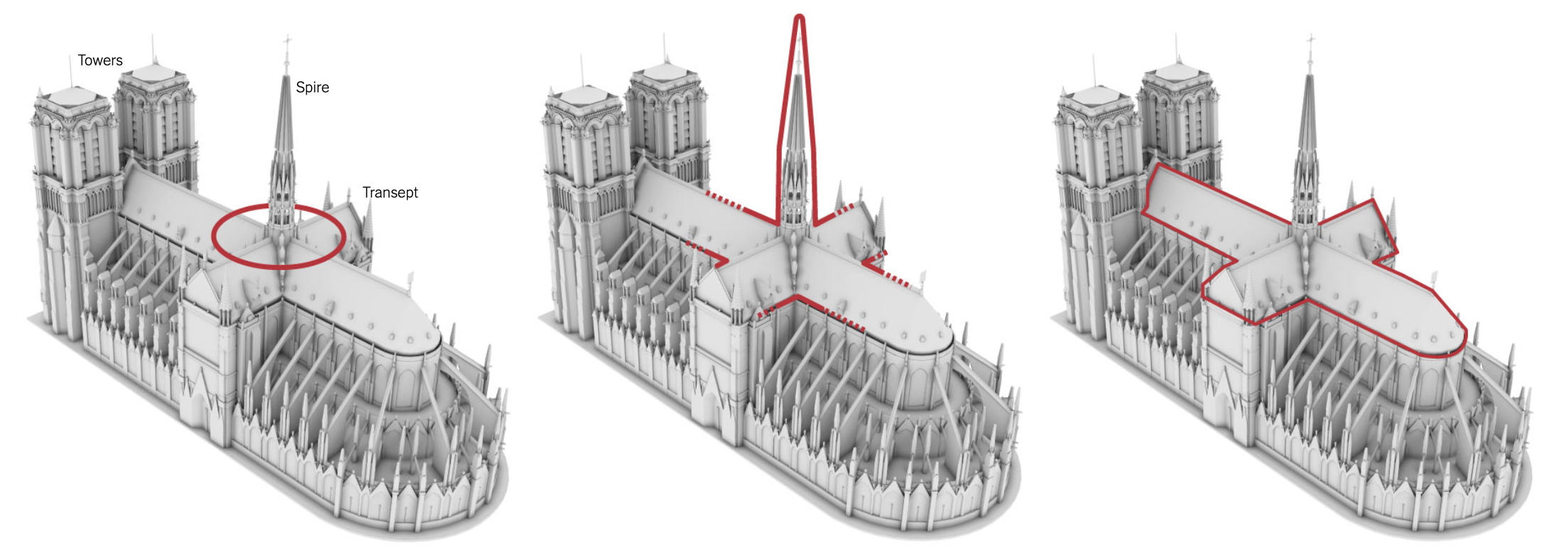

While reenactments might bring animations to mind, there are plenty of strong static “play-by-plays” out there, such as “How the Notre Dame Cathedral Fire Spread,” another example from NYT. Static images provide us a play-by-play breakdown of how the fire began and spread, and how French firefighters sought to combat the fire. Each moment provides us with a beautifully drawn cross-section paired with photographs of the fire, allowing us to connect what our eyes saw to the hidden and vulnerable architecture.

雖然重演可能會讓人想到動畫,但這里有很多強大的靜態“逐個播放”功能,例如“ 紐約 圣母院大教堂的火勢如何蔓延 ”,這是紐約時報的另一個例子。 靜態圖像為我們提供了火勢如何開始蔓延以及法國消防員如何撲滅大火的詳細信息。 每一個瞬間都為我們提供了精美繪制的橫截面以及火焰的照片,使我們能夠將眼睛看到的東西與隱藏的脆弱建筑聯系起來。

All too often my own tendency is to summarize events over time in a single line chart—perhaps for the above, I’d have shown some measure of fire intensity plotted at each hour. However, this reenactment parallel technique allows readers to understand what’s happening within each of those dots along a line.

我自己的趨勢常常是在單個折線圖中匯總隨時間變化的事件-也許對于上述情況,我已經展示了每小時繪制的某種火勢度量。 但是,這種重新制定并行技術使讀者可以理解沿線的每個點中正在發生的事情。

We, and our readers, don’t experience time as a line—we live in a single dot at a time, a single moment. Reenactments—and the NYT team’s storytelling in this example—let me experience each dot, enabling me to contextualize the data and the insights into the narrative almost as if I was omnisciently witnessing the fire in person.

我們和我們的讀者不會像排隊一樣體驗時間,我們一次只能住一個點。 重演以及本例中的NYT團隊的故事講述-讓我體驗到每個點,使我能夠將數據和敘述的見解上下文化,幾乎就像我全神貫注地親眼目睹火災一樣。

The few concepts I’ve outlined above are just examples. The more I dig into documentary narrative techniques, the more parallels I find to examples of excellence in data storytelling. Our mediums are different, so these parallels are never one-to-one—but the similarities are strong enough that I’m convinced we should look to the art of documentary filmmaking as our elder, with a lifetime of experience to share.

我上面概述的幾個概念僅僅是示例。 我越是研究文獻敘事技術,就越會發現與數據敘事卓越案例的相似之處。 我們的媒體是不同的,所以這些相似之處永遠不會一對一,但相似之處足夠強大,我深信我們應該以長輩的身份去欣賞紀錄片電影制作藝術,并分享一生的經驗。

Perhaps the most poignant opportunity to see the similarities between documentaries and data storytelling comes from a quote by five-time Emmy Award winning documentary filmmaker Ken Burns:

看到紀錄片和數據故事敘述之間相似之處的最可悲的機會可能是五次獲得艾美獎的紀錄片導演肯·伯恩斯 ( Ken Burns) 的名言 :

I realized very early on that the laws of storytelling also apply to the documentary. That instead of the documentary necessarily being didactic and educational and, you know, politically advocating, it could also just tell a story using the same expositional tools that a feature film would. And then you’ve got the possibility of moving people at that same level. And you have the added advantage of it being true. Steven Spielberg and I obey the same laws of storytelling. And the only difference is he can make shit up, and I can’t.

我很早就意識到講故事的法律也適用于紀錄片。 那不是紀錄片一定是有說服力的和教育性的,而且從政治上講,您知道,它也可以使用與故事片相同的展示工具來講述一個故事。 然后,您就有可能將人們轉移到同一水平。 而且您還有一個附加的優點,那就是它是真實的。 史蒂芬·斯皮爾伯格和我遵守同樣的故事定律。 唯一的區別是他可以彌補,我不能。

Love y’all.

愛你們

翻譯自: https://medium.com/nightingale/visualize-data-action-what-data-viz-has-in-common-with-documentaries-6c5de17bd077

數據可視化 信息可視化

本文來自互聯網用戶投稿,該文觀點僅代表作者本人,不代表本站立場。本站僅提供信息存儲空間服務,不擁有所有權,不承擔相關法律責任。 如若轉載,請注明出處:http://www.pswp.cn/news/389246.shtml 繁體地址,請注明出處:http://hk.pswp.cn/news/389246.shtml 英文地址,請注明出處:http://en.pswp.cn/news/389246.shtml

如若內容造成侵權/違法違規/事實不符,請聯系多彩編程網進行投訴反饋email:809451989@qq.com,一經查實,立即刪除!

:解析)