注釋標記的原則

By Emily Saltz, Tommy Shane, Victoria Kwan, Claire Leibowicz, Claire Wardle

埃米莉·薩爾茨 ( Emily Saltz) , 湯米·沙恩 ( Tommy Shane) , 關 穎琳 ( Victoria Kwan) , 克萊爾·萊博維奇 ( Claire Leibowicz) , 克萊爾·沃德 ( Claire Wardle)

貼標簽或不貼標簽:標簽何時可能造成弊大于利? (To label or not to label: When might labels cause more harm than good?)

Manipulated photos and videos flood our fragmented, polluted, and increasingly automated information ecosystem, from a synthetically generated “deepfake,” to the far more common problem of older images resurfacing and being shared with a different context. While research is still limited, there is some empirical support to show visuals tend to be both more memorable and more widely shared than text-only posts, heightening their potential to cause real-world harm, at scale — just consider the numerous audiovisual examples in this running list of hoaxes and misleading posts about police brutality protests in the United States. In response, what should social media platforms do? Twitter, Facebook, and others have been working on new ways to identify and label manipulated media.

處理過的照片和視頻充斥著我們分散,污染和日益自動化的信息生態系統,從合成生成的“ deepfake”,到更常見的舊圖像重新出現并與其他環境共享的問題。 盡管研究仍很有限,但有一些經驗支持表明視覺效果比純文字信息更容易讓人記憶深刻 , 分享更多 ,從而擴大了它們對現實世界造成危害的潛力,請考慮一下其中的眾多視聽實例。有關美國警察暴行抗議的惡作劇和誤導性帖子列表 。 作為回應,社交媒體平臺應該做什么? Twitter,Facebook和其他公司一直在研究識別和標記可操縱媒體的新方法。

As the divisive reactions to Twitter’s recent decision to label two of Trump’s misleading and incendiary tweets demonstrate, label designs aren’t applied in a vacuum. In one instance, the platform appended a label under a tweet that contained incorrect information about California’s absentee ballot process, encouraging readers to click through and “Get the facts about mail-in ballots.” In the other instance, Twitter replaced the text of a tweet referring to shooting of looters with a label that says, “This tweet violates the Twitter Rules about glorifying violence.” (Determining that it was in the public interest for the tweet to remain accessible, however, this label allowed users the option to click through to the original text.)

正如對Twitter最近決定標記特朗普的兩個誤導性和煽動性推文的決定所產生的分歧React所表明的那樣,標簽設計并不是在真空中應用的。 在一個實例中,該平臺在一條推文下添加了一個標簽,其中包含有關加利福尼亞州缺席投票程序的錯誤信息,從而鼓勵讀者點擊并“獲得有關郵寄投票的事實”。 在另一種情況下,Twitter用一個標有“ 槍擊劫掠者 ”的推文替換了標簽,上面寫著“此推文違反了推崇暴力的推特規則”。 (確定此推文是否可訪問符合公共利益,不過,該標簽允許用戶選擇單擊以查看原始文本。)

These examples show that the world notices and reacts to the way platforms label content — including President Trump himself, who has directly responded to the labels. With every labeling decision, the ‘fourth wall’ of platform neutrality is swiftly breaking down. Behind it, we can see that every label — whether for text, images, video, or a combination — comes with a set of assumptions that must be independently tested against clear goals and transparently communicated to users. As each platform uses its own terminology, visual language, and interaction design for labels, with application informed respectively by their own detection technologies, internal testing, and theories of harm (sometimes explicit, sometimes ad hoc) — the end result is a largely incoherent landscape of labels leading to unknown societal effects.

這些示例表明,世界注意到平臺對內容加標簽的方式并做出了React,包括直接對標簽做出回應的特朗普總統本人。 通過每項標簽決策,平臺中立性的“第四壁”正在Swift瓦解。 在其背后,我們可以看到每個標簽(無論是文本,圖像,視頻還是組合標簽)都帶有一組假設,這些假設必須針對明確的目標進行獨立測試,并以透明的方式傳達給用戶。 由于每個平臺使用其自己的術語,視覺語言和標簽交互設計,其應用分別通過其自身的檢測技術,內部測試和傷害理論(有時是明確的,有時是臨時的)來告知,因此最終結果在很大程度上是不一致的標簽的景觀導致未知的社會影響。

At the Partnership on AI and First Draft, we’ve been collaboratively studying how digital platforms might address manipulated media with empirically-tested and responsible design solutions. Though definitions of “manipulated media” vary, we define it as any image or video with content or context edited along the “cheap fake” to “deepfake” spectrum (Data & Society) with the potential to mislead and cause harm. In particular, we’re interrogating the potential risks and benefits of labels: language and visual indicators that notify users about manipulation. What are best practices for digital platforms applying (or not applying) labels to manipulated media in order to reduce mis/disinformation’s harms?

在AI和初稿合作伙伴計劃中,我們一直在協作研究數字平臺如何通過經過實驗測試和負責任的設計解決方案來處理受控媒體。 盡管“操縱的媒體”的定義有所不同,但我們將其定義為具有從“廉價假貨”到“深造”頻譜 (數據和社會)編輯的內容或上下文的任何圖像或視頻,可能會誤導和造成傷害。 特別是,我們正在調查標簽的潛在風險和收益:向用戶通知操作的語言和視覺指示器。 為了減少錯誤/虛假信息的危害,數字平臺將最佳實踐應用于(或不應用于)受控媒體的最佳做法是什么?

我們發現了什么 (What we’ve found)

In order to reduce mis/disinformation’s harm to society, we have compiled the following set of principles for designers at platforms to consider for labeling manipulated media. We also include design ideas for how platforms might explore, test, and adapt these principles for their own contexts. These principles and ideas draw from hundreds of studies and many interviews with industry experts, as well as our own ongoing user-centric research at PAI and First Draft (more to come on this later this year).

為了減少錯誤/虛假信息對社會的危害,我們為平臺的設計人員編制了以下原則,以供他們考慮對受控媒體進行標記。 我們還包括有關平臺如何根據自己的環境探索,測試和調整這些原理的設計思想。 這些原則和思想來自數百項研究和對行業專家的多次采訪,以及我們正在進行的針對PAI和First Draft的以用戶為中心的研究(更多信息將在今年晚些時候發布)。

Ultimately, labeling is just one way of addressing mis/disinformation: how does labeling compare to other approaches, such as removing or downranking content? Platform interventions are so new that there isn’t yet robust public data on their effects. But researchers and designers have been studying topics of trust, credibility, information design, media perception, and effects for decades, providing a rich starting point of human-centric design principles for manipulated media interventions.

最終,標記只是解決錯誤/虛假信息的一種方法:標記與其他方法(例如刪除或降級內容)相比如何? 平臺干預非常新,以至于尚沒有關于其影響的可靠公共數據。 但是數十年來,研究人員和設計師一直在研究信任,可信度,信息設計,媒體感知和效果等主題,為操縱媒體干預提供了以人為本的設計原則的豐富起點。

原則 (Principles)

1.不要對錯誤/虛假信息引起不必要的關注 (1. Don’t attract unnecessary attention to the mis/disinformation)

Although assessing harm from visual mis/disinformation can be difficult, there are cases where the severity or likelihood of harm is so great — for example, when the manipulated media poses a threat to someone’s physical safety — that it warrants an intervention stronger than a label. Research shows that even brief exposure has a “continued influence effect” where the memory trace of the initial post cannot be unremembered [1]. With images and video especially sticky in memory, due to “the picture superiority effect” [2] — the best tactic for reducing belief in such instances of manipulated media may be outright removal or downranking.

盡管很難評估視覺錯誤/虛假信息造成的傷害,但在某些情況下,傷害的嚴重性或可能性如此之大(例如,當被操縱的媒體對某人的人身安全構成威脅時),它需要采取的干預措施要強于標簽。 研究表明,即使是短暫的暴露也具有“持續的影響效應”,在該效應中,最初帖子的記憶軌跡無法被記住[1]。 由于“圖片優勢” [2],圖像和視頻在內存中特別發粘,因此,減少對此類受控媒體實例的置信度的最佳策略可能是徹底刪除或降級。

Another way of reducing exposure may be the addition of an overlay. This approach is not without risk, however: the extra interaction (clicking to remove the overlay) should not be framed in a way that creates a “curiosity gap” for the user, making it tempting to click to reveal the content. Visual treatments may want to make the posts less noticeable, interesting, and visually salient compared to other content — for example, using grayscale, or reducing the size of the content.

減少曝光的另一種方法可能是添加覆蓋層。 但是,這種方法并非沒有風險:額外的交互(單擊以刪除疊加層)不應以給用戶造成“好奇心差距”的方式進行構架,以使其誘使單擊以顯示內容。 與其他內容相比,視覺處理可能希望使帖子不那么引人注目,更有趣并且在視覺上更加醒目-例如,使用灰度或減小內容的大小。

2.使標簽引人注目且易于處理 (2. Make labels noticeable and easy to process)

A label can only be effective if it’s noticed in the first place. How well a fact-check works depends on attention and timing: debunks are most effective when noticed simultaneously with the mis/disinformation, and are much less effective if noticed or displayed after exposure. Applying this lesson, labels need to be as or more noticeable than the manipulated media, so as to inform the user’s initial gut reaction — what’s known as “system 1” thinking [1], [2], [3], [4], [5].

只有首先注意到標簽,標簽才有效。 事實檢查的效果取決于注意力和時間安排:當與錯誤/虛假信息同時被發現時,竊聽是最有效的,而在暴露后被發現或顯示時,竊聽的效果則要差得多。 應用本課時,標簽必須比被操縱的媒體更引人注目,以便告知用戶最初的腸道React-所謂的“系統1”思維[1],[2],[3],[4] ,[5]。

From a design perspective, this means starting with accessible graphics and language. An example of this is how The Guardian prominently highlights the age of old articles.

從設計的角度來看,這意味著從可訪問的圖形和語言開始。 這方面的一個例子是《衛報》如何突出強調舊物品的時代。

The risk of label prominence, however, is that it could draw the user’s attention to misinformation that they may not have noticed otherwise. One potential way to mitigate that risk would be to highlight the label, e.g. through color or animation, only if the user dwells on or interacts with the content, indicating interest. Indeed, Facebook appears to have embraced this approach by animating their context button only if a user dwells on a post.

然而,標簽突出的風險是,它可能會引起用戶注意他們可能沒有注意到的錯誤信息。 減輕這種風險的一種可能方法是僅在用戶停留在內容上或與內容互動時(例如,通過顏色或動畫)突出顯示標簽,以表示興趣。 確實,Facebook僅在用戶停留在帖子上時才通過為其上下文按鈕添加動畫來采用這種方法。

Another opportunity for making labels easy to process might be to minimize other cues in contrast, such as social media reactions and endorsement. Research has found that exposure to social engagement metrics increases vulnerability to misinformation [6]. In minimizing other cues, platforms may be able to nudge users to focus on the critical task at hand: accurately assessing the credibility of the media.

使標簽易于處理的另一個機會可能是盡量減少其他暗示,例如社交媒體的React和認可。 研究發現,接觸社會參與指標會增加錯誤信息的脆弱性[6]。 在最小化其他提示的情況下,平臺可能能夠促使用戶專注于眼前的關鍵任務:準確評估媒體的信譽。

3.鼓勵情緒上的思考和懷疑 (3. Encourage emotional deliberation and skepticism)

In addition to being noticeable and easily understood, a label should encourage a user to evaluate the media at hand. Multiple studies have shown that the more one can be critically and skeptically engaged in assessing content, the more accurately one can judge the information [1], [2], [5], [7]. In general, research indicates people are more likely to trust misleading media due to “lack of reasoning, rather than motivated reasoning” [8]. Thus, deliberately nudging people to engage in reasoning may actually increase accurate recollection of claims [1].

除了引人注目和易于理解之外,標簽還應鼓勵用戶評估手頭的媒體。 多項研究表明,越能批判和懷疑地參與評估內容,就越能準確地判斷信息[1],[2],[5],[7]。 總的來說,研究表明,人們由于“缺乏推理,而不是動機推理”而更容易相信誤導性媒體[8]。 因此,故意促使人們參與推理實際上可以增加對索賠的準確回憶[1]。

One tactic to encourage deliberation, already employed by platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, requires users to engage in an extra interaction like a click before they can see the visual misinformation. This additional friction builds in time for reflection and may help the user to shift into a more skeptical mindset, especially if used alongside prompts that prepare the user to critically assess the information before viewing content [1], [2]. For example, labels could ask people “Is the post written in a style that I expect from a professional news organization?” before reading the content [9].

Facebook,Instagram和Twitter等平臺已經采用的一種鼓勵商議的策略是,要求用戶進行額外的互動,例如單擊,然后才能看到視覺錯誤信息。 這種額外的摩擦會及時產生反映的效果,并可能幫助用戶轉變為更加懷疑的心態,尤其是與提示結合使用時,提示用戶可以在查看內容[1],[2]之前嚴格評估信息。 例如,標簽可能會問人們“帖子是按照我期望的專業新聞機構的風格撰寫的嗎?” 在閱讀內容之前[9]。

4.提供更多信息的靈活訪問 (4. Offer flexible access to more information)

During deliberation, different people may have different questions about the media. Access to these additional details should be provided, without compromising the readability of the initial label. Platforms should consider how a label can progressively disclose more detail as the user interacts with it, enabling users to follow flexible analysis paths according to their own lines of critical consideration [10].

在審議過程中,不同的人可能對媒體有不同的疑問。 應該提供對這些附加詳細信息的訪問,而不會損害初始標簽的可讀性。 平臺應考慮標簽如何在用戶與標簽交互時逐步披露更多細節,從而使用戶能夠根據自己的重要考慮因素遵循靈活的分析路徑[10]。

What kind of detail might people want? This question warrants further design exploration and testing. Some possible details may include the capture and edit trail of media; information on a source and its activity; and general information on media manipulation tactics, ratings, and mis/disinformation. Interventions like Facebook’s context button can provide this information through multiple tabs or links to pages with additional details.

人們可能想要什么樣的細節? 這個問題值得進一步的設計探索和測試。 一些可能的細節可能包括媒體的捕獲和編輯軌跡。 有關來源及其活動的信息; 以及有關媒體操縱策略,評級和錯誤/虛假信息的一般信息。 諸如Facebook的上下文按鈕之類的干預措施可以通過多個選項卡或具有更多詳細信息的頁面鏈接來提供此信息。

5.在上下文中使用一致的標簽系統 (5. Use a consistent labeling system across contexts)

On platforms it is crucial to consider not just the effects of a label for a particular piece of content, but across all media encountered — labeled and unlabeled. Recent research suggests that labeling only a subset of fact-checkable content on social media may do more harm than good by increasing users’ beliefs in the accuracy of unlabeled claims. This is because a lack of a label may imply accuracy in cases where the content may be false, but not labeled, known as “the implied truth effect” [11]. The implied truth effect is perhaps the most profound challenge for labeling, as it is impossible for fact-checkers to check all media posted to platforms. Because of this limitation in fact-checking at scale, fact-checked media on platforms will always be a subset, and labeling that subset will always have the potential to boost the perceived credibility of all other unchecked media, regardless of its accuracy.

在平臺上,至關重要的是,不僅要考慮標簽對特定內容的影響,而且還要考慮所遇到的所有媒體(帶標簽和不帶標簽)。 最近的研究表明,在社交媒體上僅標記事實可檢查內容的一部分可能會增加用戶對未標記主張的準確性的信念,弊大于利。 這是因為在內容可能是錯誤的但未標記的情況下,缺少標簽可能意味著準確性,這被稱為“隱含真相效應” [11]。 隱含的真相效應可能是標簽方面最嚴峻的挑戰,因為事實檢查人員不可能檢查發布到平臺上的所有媒體。 由于在大規模事實檢查中存在此限制,因此平臺上經過事實檢查的媒體將始終是子集,并且標記該子集將始終具有提高所有其他未經檢查的媒體的可信度的潛力,無論其準確性如何。

Platform designs should, therefore, aim to minimize this “implied truth effect” at a cross-platform, ecosystem level. This demands much more exploration and testing across platforms. For example, what might be the effects of labeling all media as “unchecked” by default?

因此,平臺設計應旨在在跨平臺的生態系統級別上最小化這種“隱含的真相效應”。 這需要跨平臺進行更多的探索和測試。 例如,默認情況下將所有媒體標記為“未選中”會產生什么影響?

Further, consistent systems of language and iconography across platforms enable users to form a mental model of media that they can extend to accurately judge media across contexts, for example, by understanding that a “manipulated” label means the same thing whether it’s on YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter. Additionally, if a design language is consistent across platforms, it may help users more rapidly recognize issues over time as it becomes more familiar, and thus and easier to process and trust (c.f. Principle 2).

此外,跨平臺的一致語言和圖像系統使用戶能夠形成一種媒體的心理模型,他們可以擴展該模型以準確判斷各種情況下的媒體,例如,通過了解“操縱的”標簽在YouTube上的含義是相同的, Facebook或Twitter。 此外,如果一種設計語言在各個平臺之間是一致的,則隨著時間變得越來越熟悉,它可以幫助用戶隨著時間的流逝更快地識別問題,從而更輕松地進行處理和信任(參見原則2)。

6.重復事實,而不是虛假事實 (6. Repeat the facts, not the falsehoods)

It’s important not just to debunk what’s false, but to ensure that users come away with a clear understanding of what’s accurate. It’s risky to display labels that describe media in terms of the false information without emphasizing what is true. Familiar things seem more true, meaning every repetition of the mis/disinformation claim associated with a visual risks imprinting that false claim deeper in memory — a phenomenon known as “the illusory truth effect” or the “myth-familiarity boost” [1].

重要的是,不僅要揭穿虛假內容,而且要確保用戶清楚了解準確內容。 這是有風險的描述中的虛假信息方面沒有媒體強調什么是真正的顯示標簽。 熟悉的事物看起來更真實,這意味著與視覺相關的錯誤/虛假信息主張的每一次重復都會使錯誤的主張銘刻在記憶的更深處,這種現象被稱為“虛幻的真實效果”或“神話般的熟習感” [1]。

Rather than frame the label in terms of what’s inaccurate, platforms should elevate the accurate details that are known. Describe the accurate facts rather than simply rate the media in unspecific terms while avoiding repeating the falsehoods [1], [2], [3]. If it’s possible, surface clarifying metadata, such as the accurate location, age, and subject matter of a visual.

平臺不應該根據不準確的內容來構架標簽,而應該提升已知的準確細節。 描述準確的事實,而不是簡單地用非特定術語對媒體進行評級,同時避免重復錯誤的說法[1],[2],[3]。 如果可能的話,表面澄清的元數據,例如視覺的準確位置,年齡和主題。

7.使用非對抗性的,移情的語言 (7. Use non-confrontational, empathetic language)

The language on a manipulated media label should be non-confrontational, so as not to challenge an individual’s identity, intelligence, or worldview. Though the research is mixed, some studies have found that in rare cases, confrontational language risks triggering the “backfire effect,” where an identity-challenging fact-check may further entrench belief in a false claim [13], [14]. Regardless, it helps to adapt and translate the label to the person. As much as possible, meet people where they are by framing the correction in a way that is consistent with the users’ worldview. Highlighting accurate aspects of the media that are consistent with their preexisting opinions and cultural context may make the label easier to process [1], [12].

受控媒體標簽上的語言應具有非對抗性,以免挑戰個人的身份,智慧或世界觀。 盡管研究結果參差不齊 ,但一些研究發現,在極少數情況下,對抗性語言風險會引發“事與愿違的后果”,在這種情況下,具有挑戰性的事實檢查可能會進一步鞏固對虛假主張的信念[13],[14]。 無論如何,它有助于使標簽適應并翻譯給人。 盡可能以與用戶的世界觀相一致的方式來制定修正方案,與他們所處的地方相識。 突出顯示媒體與其先前觀點和文化背景一致的準確方面,可能會使標簽更易于處理[1],[12]。

Design-wise, this has implications for the language of the label and label description. While the specific language should be tested and refined with audiences, language choice does matter. A 2019 study found that when adding a tag to false headlines on social media, the more descriptive “Rated False” tag was more effective at reducing belief in the headline’s accuracy than a tag that said “Disputed” [15]. Additionally, there is an opportunity to build trust by using adaptive language and terminology consistent with other sources and framings of an issue that a user follows and trusts. For example, “one study found that Republicans were far more likely to accept an otherwise identical charge as a ‘carbon offset’ than as a ‘tax,’ whereas the wording has little effect on Democrats or Independents (whose values are not challenged by the word ‘tax;’ Hardisty, Johnson, & Weber, 2010)” [1].

在設計方面,這對標簽和標簽描述的語言有影響。 雖然應該與受眾一起測試和完善特定的語言,但語言的選擇確實很重要。 一項2019年的研究發現,在社交媒體的虛假標題上添加標簽時,更具描述性的“定級虛假”標簽比說“有爭議”的標簽更有效地降低了對標題準確性的信念[15]。 此外,還有機會使用與用戶關注和信任的問題的其他來源和框架相一致的自適應語言和術語來建立信任。 例如,“一項研究發現,共和黨人更可能接受其他相同的收費作為“碳補償”,而不是“稅收”,而措辭對民主黨或獨立人士的影響很小(其價值不受“民主黨”或“獨立黨”的挑戰)。單詞'tax;'Hardisty,Johnson,&Weber,2010)” [1]。

8.強調用戶信任的可靠反駁來源 (8. Emphasize credible refutation sources that the user trusts)

The effectiveness of a label to influence user beliefs may depend on the source of the correction. To be most effective, a correction should be told by people or groups the user knows and trusts [1], [16], rather than a central authority or authorities that the user may distrust. Research indicates that when it comes to the source of a fact-check, people value trustworthiness over expertise–that means a favorite celebrity or YouTube personality might be a more resonant messenger than an unfamiliar fact-checker with deep expertise.

標簽影響用戶信念的有效性可能取決于更正的來源。 為了更有效,應該由用戶認識并信任的人員或團體告知更正[1],[16],而不是用戶可能不信任的中央機構。 研究表明,在事實核查的來源上,人們重視可信度,而不是專業知識。這意味著,與不熟悉且具有深厚專業知識的事實檢查員相比,最喜歡的名人或YouTube個性可能更能引起人們的共鳴。

If a platform has access to correction information from multiple sources, the platform should highlight sources the user trusts, for example promoting sources that the user has seen and/or interacted with before. Additionally, platforms could highlight related, accurate articles from publishers the user follows and interacts with, or promote comments from friends that are consistent with the fact-check. This strategy may have the additional benefit of minimizing potential retaliation threats to publishers and fact-checkers — i.e. preventing users from personally harassing sources they distrust.

如果平臺可以從多個來源訪問校正信息,則該平臺應突出顯示用戶信任的來源,例如,提升用戶之前已經看到和/或與之交互的來源。 此外,平臺可以突出顯示用戶關注并與之交互的發布者提供的相關,準確的文章,或者促進來自朋友的與事實核對一致的評論。 該策略可能具有額外的好處,即可以最大程度地減少對發布者和事實檢查者的報復威脅,即防止用戶親自騷擾他們不信任的來源。

9.對標簽的局限性保持透明,并提供一種對抗它的方法 (9. Be transparent about the limitations of the label and provide a way to contest it)

Given the difficulty of ratings and displaying labels at scale for highly subjective, contextualized user-generated content, a user may have reasonable disagreements with a label’s conclusion about a post. For example, Dr. Safiya Noble, a professor of Information Studies at UCLA, and author of the book “Algorithms of Oppression,” recently shared a Black Lives Matter-related post on Instagram that she felt was unfairly flagged as “Partly False Information.”

鑒于很難對高度主觀的,上下文相關的用戶生成的內容進行評級和大規模顯示標簽,因此用戶可能會對標簽關于帖子的結論有合理的分歧。 例如,加州大學洛杉磯分校(UCLA)信息研究教授,《壓迫算法》(Algorithms of Oppression)的作者薩菲亞·諾布爾(Safiya Noble)博士最近在Instagram上分享了與黑生活問題相關的帖子 ,她認為自己被不公平地標記為“部分錯誤的信息”。 ”

As a result, labels should offer swift recourse to contest labels and provide feedback if users feel labels have been inappropriately applied, similar to interactions for reporting harmful posts.

結果,標簽應該提供快速的競賽標簽資源,并且如果用戶覺得標簽使用不當,則應該提供反饋,類似于報告有害帖子的交互。

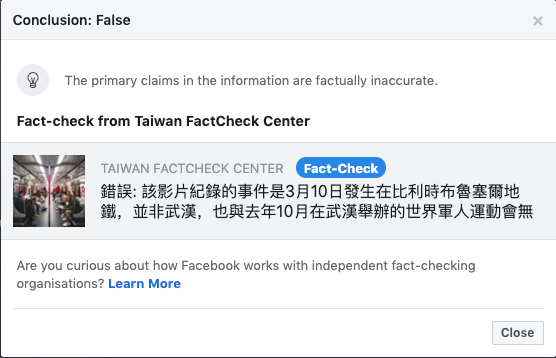

Additionally, platforms should share the reasoning and process behind the label’s application. If an instance of manipulated media was identified and labeled through automation, for example, without context-specific vetting by humans, that should be made clear to users. This also means linking the label to an explanation that not only describes how the media was manipulated, but who made that determination and should be held accountable. Facebook’s labels, for example, will say that the manipulated media was identified by third-party fact-checkers, and clicking the “See Why” button opens up a preview of the actual fact check.

此外,平臺應共享標簽應用程序背后的推理和過程。 例如,如果通過自動化識別并標記了可操縱媒體的實例,而沒有人進行特定于上下文的審查,則應向用戶明確。 這也意味著將標簽鏈接到一個說明上,該說明不僅描述了媒體是如何被操縱的,而且是由誰做出決定的,應當追究責任。 例如,Facebook的標簽將說被操縱的媒體是由第三方事實檢查員識別的,然后單擊“查看原因”按鈕可打開實際事實檢查的預覽。

10.用多種視覺角度填充缺少的替代方案 (10. Fill in missing alternatives with multiple visual perspectives)

Experiments have shown that a debunk is more effective at dislodging incorrect information from a person’s mind when it provides an alternative explanation to take the place of the faulty information [3]. Thus, labels for manipulated media should present alternatives that preempt the user’s inevitable question: what really happened then?

實驗表明,當debunk提供替代性解釋來代替錯誤信息時,它可以更有效地從人的思想中消除錯誤信息[3]。 因此,用于可操縱媒體的標簽應提供替代方案,以取代用戶不可避免的問題:那時到底發生了什么?

Recall that the “picture superiority effect” means images are more likely to be remembered than words. If possible, fight the misleading visuals with accurate visuals. This can be done by displaying multiple photo and video perspectives in order to visually reinforce the accurate event [5]. Additionally, platforms could explore displaying “related images,” for example by surfacing reverse image search results, to provide visually similar images and videos possibly from the same event.

回想一下,“圖片優勢效果”意味著圖像比文字更容易被記住。 如有可能,請以準確的視覺效果與誤導性視覺效果作斗爭。 這可以通過顯示多個照片和視頻透視圖來完成,以便在視覺上增強準確的事件[5]。 此外,平臺可以探索顯示“相關圖像”,例如通過顯示反向圖像搜索結果,以提供可能來自同一事件的視覺相似圖像和視頻。

11.幫助用戶識別和理解特定的操縱策略 (11. Help users identify and understand specific manipulation tactics)

Research shows that people are poor at identifying manipulations in photos and videos: In one study measuring perception of photos doctored in various ways, such as airbrushing and perspective distortion, people could only identify 60% of images as manipulated. They were even worse at telling where exactly a photo was edited, accurately locating the alterations only 45% of the time [18].

研究表明,人們不擅長識別照片和視頻中的操作:在一項對以各種方式(例如噴槍和透視畸變)篡改的照片的感知度的研究中,人們只能識別出60%的圖像是被操作的。 他們甚至更不敢說出照片的確切編輯位置,僅在45%的時間內準確地定位了更改[18]。

Additionally, even side-by-side presentation of manipulated vs. original visuals may not be enough without extra indications of what’s been edited, due to “change blindness,” a phenomenon where people fail to notice major changes to visual stimuli: “It often requires a large number of alternations between the two images before the change can be identified…[which] persists when the original and changed images are shown side by side” [19].

此外,由于“變化盲”,人們無法注意到視覺刺激的重大變化,即使沒有對編輯內容的額外指示,即使是并排呈現的視覺效果也可能不夠。需要先在兩個圖像之間進行大量交替,然后才能識別出更改... [當同時顯示原始圖像和更改后的圖像時,[這]仍然存在” [19]。

These findings indicate that manipulations need to be highlighted in a way that is easy to process in comparison to any available accurate visuals. [18], [19]. Showing manipulations side-by-side to an unmanipulated original may be useful especially alongside annotated sections of where an image or video has been edited, and including explanations of manipulations in order to aid future recognition.

這些發現表明,與任何可用的準確視覺效果相比,都需要以一種易于處理的方式突出顯示操作。 [18],[19]。 與未處理的原件并排顯示操作可能會很有用,尤其是在已編輯圖像或視頻的帶注釋的部分旁邊,并包括對操作的說明以幫助將來識別。

In general, platforms should provide specific corrections, emphasizing the factual information in close proximity to where the manipulations occur — for example, highlighting alterations in context of the specific, relevant points of the video [20]. Or, if a video clip has been taken out of context, show how. For example, when an edited video of Bloomberg’s Democratic debate performance was misleadingly cut together with long pauses and cricket audio to indicate that his opponents were left speechless, platforms could have provided access to the original unedited debate clip and describe how and where the video was edited in order to increase user awareness of this tactic.

通常,平臺應提供特定的更正,強調與操縱發生位置非常接近的事實信息,例如,突出顯示視頻特定,相關點的上下文中的更改[20]。 或者,如果視頻剪輯已脫離上下文,請顯示操作方法。 例如,當彭博社的民主黨辯論表演的剪輯視頻誤導性地與長時間的停頓和的聲音誤導起來以表明他的對手無話可說時,平臺本可以提供對原始未經剪輯的辯論剪輯的訪問,并描述該視頻的方式和位置進行編輯,以提高用戶對此策略的了解。

12.根據用例調整和測量標簽 (12. Adapt and measure labels according to the use case)

In addition to individual user variances, platforms should consider use case variances: interventions for YouTube, where users may encounter manipulated media through searching specific topics or through the auto-play feature, might look different from an intervention on Instagram for users encountering media through exploring tags, or an intervention on TikTok, where users passively scroll through videos. Before designing, it is critical to understand how the user might land on manipulated media, and what actions the user should take as a result of the intervention.

除了個人用戶差異外,平臺還應考慮用例差異:針對YouTube的干預(用戶可能會通過搜索特定主題或通過自動播放功能來遇到可操縱的媒體),對于YouTube的干預可能看起來不同于通過探索而遇到媒體的用戶對Instagram干預。標簽或對TikTok的干預,用戶可以在其中被動地滾動瀏覽視頻。 在設計之前,至關重要的是要了解用戶可能如何落在被操縱的媒體上,以及用戶由于干預而應采取的行動。

For example, is the goal to have the user click through to more information about the context of the media? Is it to prevent users from accessing the original media (which Facebook has cited as its own metric for success)? Are you trying to reduce exposure, engagement, or sharing? Are you trying to prompt searches for facts on other platforms? Are you trying to educate the user about manipulation techniques?

例如,目標是讓用戶點擊以獲取有關媒體上下文的更多信息嗎? 是否阻止用戶訪問原始媒體( Facebook引用其為成功標準)? 您是否要減少曝光,參與或共享? 您是否要在其他平臺上提示搜索事實? 您是否正在嘗試向用戶介紹操縱技術?

Finally, labels do not exist in isolation. Platforms should consider how labels interact with other contexts and credibility indicators around a post (e.g. social cues, source verification). Clarity about the use and goals are crucial to designing meaningful interventions.

最后,標簽不是孤立存在的。 平臺應考慮標簽如何與帖子周圍的其他上下文和信譽指標交互(例如,社交線索,來源驗證)。 明確用途和目標對于設計有意義的干預措施至關重要。

這些原則只是一個起點 (These principles are just a starting point)

While these principles can serve as a starting point, they are no replacement for continued and rigorous user experience testing across diverse populations, tested in-situ in actual contexts of use. Much of this research was conducted in artificial contexts that are not ecologically valid, and as this is a nascent research area, some principles have been demonstrated more robustly than others.

雖然這些原則可以作為起點,但它們不能替代在不同人群中進行的持續且嚴格的用戶體驗測試,這些測試是在實際使用環境中進行的。 這項研究大部分是在不符合生態學原理的人工環境中進行的,并且由于這是一個新興的研究領域,因此某些原理已被更可靠地證明。

Given this, there are inevitable tensions and contradictions in the research literature around interventions. Ultimately, every context is different: abstract principles can get you to an informed concept or hypothesis, but the design details of specific implementations will surely offer new insights and opportunities for iteration toward the goals of reducing exposure to and engagement with mis/disinformation.

鑒于此,關于干預的研究文獻中不可避免地存在著緊張和矛盾。 最終,每個上下文都是不同的:抽象原理可以使您了解一個有見識的概念或假設,但是特定實現的設計細節必將為減少錯誤和虛假信息的暴露和參與的目標提供新的見解和迭代機會。

To move forward in understanding the effects of labeling requires that platforms publicly commit to the goals and intended effects of their design choices; and share their findings against these goals so as to be held accountable. For this reason, PAI and First Draft are collaborating with researchers and partners in industry to explore the costs and benefits of labeling in upcoming user experience research of manipulated media labels.

為了進一步理解標簽的效果,要求平臺公開致力于其設計選擇的目標和預期效果; 并針對這些目標分享他們的發現,以便追究責任。 因此,PAI和First Draft正在與行業的研究人員和合作伙伴合作,在即將進行的可操縱媒體標簽的用戶體驗研究中探索標簽的成本和收益。

Stay tuned for more insights into best practices around labeling (or not labeling) manipulated media, and reach out to help us thoughtfully address this interdisciplinary wicked problem space together.

請繼續關注有關標記(或不標記)操縱的媒體的最佳實踐的更多見解,并努力幫助我們深思熟慮地共同解決這一跨學科的問題空間。

引文 (Citations)

- Swire, Briony, and Ullrich KH Ecker. “Misinformation and its correction: Cognitive mechanisms and recommendations for mass communication.” Misinformation and mass audiences (2018): 195–211. 太古,布里奧尼和烏爾里希·KH·埃克。 “錯誤信息及其糾正:大眾傳播的認知機制和建議。” 虛假信息和大眾聽眾(2018):195–211。

The Legal, Ethical, and Efficacy Dimensions of Managing Synthetic and Manipulated Media https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/11/15/legal-ethical-and-efficacy-dimensions-of-managing-synthetic-and-manipulated-media-pub-80439

管理合成媒體和操縱媒體的法律,道德和功效維度https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/11/15/legal-ethical-and-efficacy-dimensions-of-managing-synthetic-and-manipulated-media- pub-80439

- Cook, John, and Stephan Lewandowsky. The debunking handbook. Nundah, Queensland: Sevloid Art, 2011. 庫克,約翰和斯蒂芬·萊萬多斯基。 揭穿手冊。 昆士蘭州Nundah:Sevloid Art,2011年。

Infodemic: Half-Truths, Lies, and Critical Information in a Time of Pandemics https://www.aspeninstitute.org/events/infodemic-half-truths-lies-and-critical-information-in-a-time-of-pandemics/

信息流行病:大流行時期的半真相,謊言和關鍵信息https://www.aspeninstitute.org/events/infodemic-half-truths-lies-and-critical-information-in-a-time-of-大流行/

The News Provenance Project, 2020 https://www.newsprovenanceproject.com/

2020年的新聞來源項目https://www.newsprovenanceproject.com/

- Avram, Mihai, et al. “Exposure to Social Engagement Metrics Increases Vulnerability to Misinformation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.04682 (2020). Avram,Mihai等。 “暴露于社會參與度指標會增加錯誤信息的脆弱性。” arXiv預印本arXiv:2005.04682(2020)。

- Bago, Bence, David G. Rand, and Gordon Pennycook. “Fake news, fast and slow: Deliberation reduces belief in false (but not true) news headlines.” Journal of experimental psychology: general (2020). Bago,Bence,David G. Rand和Gordon Pennycook。 “虛假新聞,快而慢:審議減少了對虛假(但非真實)新聞頭條的信任。” 實驗心理學雜志:一般(2020)。

- Pennycook, Gordon, and David G. Rand. “Lazy, not biased: Susceptibility to partisan fake news is better explained by lack of reasoning than by motivated reasoning.” Cognition 188 (2019): 39–50. Pennycook,Gordon和David G. Rand。 “懶惰,沒有偏見:黨派虛假新聞的易感性可以通過缺乏推理而不是有動機的推理來更好地解釋。” 認知188(2019):39–50。

- Lutzke, L., Drummond, C., Slovic, P., & árvai, J. (2019). Priming critical thinking: Simple interventions limit the influence of fake news about climate change on Facebook. Global Environmental Change, 58, 101964. Lutzke,L.,Drummond,C.,Slovic,P.,&árvai,J.(2019年)。 引發批判性思維:簡單的干預措施可以限制有關氣候變化的虛假新聞對Facebook的影響。 全球環境變化,58,101964。

- Karduni, Alireza, et al. “Vulnerable to misinformation? Verifi!.” Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces. 2019. Karduni,Alireza等。 “容易受到誤傳? 驗證!” 第24屆智能用戶界面國際會議論文集。 2019。

- Metzger, Miriam J. “Understanding credibility across disciplinary boundaries.” Proceedings of the 4th workshop on Information credibility. 2010. Metzger和MiriamJ。“了解跨學科界限的信譽。” 第四屆信息可信度研討會論文集。 2010。

- Nyhan, Brendan. Misinformation and fact-checking: Research findings from social science. New America Foundation, 2012. Nyhan,布倫丹。 錯誤信息和事實核查:來自社會科學的研究結果。 新美國基金會,2012年。

- Wood, Thomas, and Ethan Porter. “The elusive backfire effect: Mass attitudes’ steadfast factual adherence.” Political Behavior 41.1 (2019): 135–163. 伍德,托馬斯和伊桑·波特。 “難以捉摸的適得其反的效果:大眾態度堅定不移地堅持事實。” 政治行為41.1(2019):135–163。

- Nyhan, Brendan, and Jason Reifler. “When corrections fail: The persistence of political misperceptions.” Political Behavior 32.2 (2010): 303–330. Nyhan,Brendan和Jason Reifler。 “當糾正失敗時:政治誤解的持續存在。” 政治行為32.2(2010):303-330。

- Clayton, Katherine, et al. “Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media.” Political Behavior (2019): 1–23. 克萊頓,凱瑟琳等人。 “假新聞的真正解決方案? 衡量一般警告和事實檢查標簽在減少對社交媒體上虛假故事的信任方面的有效性。” 政治行為(2019):1-23。

- Badrinathan, Sumitra, Simon Chauchard, and D. J. Flynn. “I Don’t Think That’s True, Bro!.” Badrinathan,Sumitra,Simon Chauchard和DJ Flynn。 “我認為那不是真的,兄弟!”

Ticks or It Didn’t Happen: Confronting Key Dilemmas In Authenticity Infrastructure For Multimedia, WITNESS (2019) https://lab.witness.org/ticks-or-it-didnt-happen/

壁壘還是沒有發生:面對多媒體真實性基礎架構中的關鍵難題,WITNESS(2019) https://lab.witness.org/ticks-or-it-didnt-happen/

- Nightingale, Sophie J., Kimberley A. Wade, and Derrick G. Watson. “Can people identify original and manipulated photos of real-world scenes?.” Cognitive research: principles and implications 2.1 (2017): 30. Nightingale,Sophie J.,Kimberley A.Wade和Derrick G.Watson。 “人們可以識別真實場景的原始照片和操縱過的照片嗎?”。 認知研究:原理與意義2.1(2017):30。

- Shen, Cuihua, et al. “Fake images: The effects of source, intermediary, and digital media literacy on contextual assessment of image credibility online.” new media & society 21.2 (2019): 438–463. 沉翠華,等。 “偽造圖像:來源,中介和數字媒體素養對在線圖像可信度的上下文評估的影響。” 新媒體與社會21.2(2019):438–463。

- Diakopoulos, Nicholas, and Irfan Essa. “Modulating video credibility via visualization of quality evaluations.” Proceedings of the 4th workshop on Information credibility. 2010. Diakopoulos,Nicholas和Irfan Essa。 “通過可視化質量評估來調節視頻可信度。” 第四屆信息可信度研討會論文集。 2010。

翻譯自: https://medium.com/swlh/it-matters-how-platforms-label-manipulated-media-here-are-12-principles-designers-should-follow-438b76546078

注釋標記的原則

本文來自互聯網用戶投稿,該文觀點僅代表作者本人,不代表本站立場。本站僅提供信息存儲空間服務,不擁有所有權,不承擔相關法律責任。 如若轉載,請注明出處:http://www.pswp.cn/news/275710.shtml 繁體地址,請注明出處:http://hk.pswp.cn/news/275710.shtml 英文地址,請注明出處:http://en.pswp.cn/news/275710.shtml

如若內容造成侵權/違法違規/事實不符,請聯系多彩編程網進行投訴反饋email:809451989@qq.com,一經查實,立即刪除!

![[轉]讓你賺大錢成富翁的4個投資習慣](http://pic.xiahunao.cn/[轉]讓你賺大錢成富翁的4個投資習慣)

)

)