zoom視頻會議官網

第二部分:房間的創造力 (Part Two: The Creativity of Rooms)

In Part One I shared thoughts on how virtual spaces can often leave little room to embody our most human selves. The lack of a public sphere that parallels our shared public experiences on a city street, a public square, and a sporting event leaves an emptiness that can only be filled by the return of such spaces to our increasingly private lives during the pandemic. Part Two of the essay focuses on the design of rooms in virtual spaces. By looking at the architecture and design of our cherished physical rooms, we can learn how to make our Zoom “rooms” more fulfilling.

在第一部分中,我分享了有關虛擬空間通常如何留出很少空間來體現我們最人類的自我的想法。 缺乏公共場所,無法與我們在城市街道,公共廣場和體育賽事上共享的公共體驗相提并論,這使得這種空虛只能通過在大流行期間將這些空間恢復為我們日益私人化的生活來填補。 本文的第二部分重點介紹虛擬空間中的房間設計。 通過查看我們珍愛的物理房間的體系結構和設計,我們可以學習如何使Zoom“房間”更加充實。

Take your eyes from the screen for a moment and look around wherever you are. Are you in a room? The majority of our day takes place inside rooms. Our private rooms have taken on greater significance now as they envelope our entire spatial being within a “shelter in place” reality. As the number of rooms we experience shrinks and the time in those few rooms expands, things we often take for granted in those rooms come into sharper focus: colours, natural light, materials, furnishings, and textures.

將您的眼睛從屏幕上移開一會兒,環顧四周。 你在房間嗎 我們大部分時間都在房間內進行。 現在,我們的私人房間具有更大的意義,因為它們將我們的整個空間都包裹在“就地庇護”現實中。 隨著我們所體驗的房間數量的減少和那幾個房間的時間的增加,我們在這些房間中通常認為理所當然的事情變得更加突出:色彩,自然光,材料,家具和質感。

The unspirited design of our virtual video conferencing rooms is becoming visceral for many of us the more time we spend inside them. Undoubtedly “Zoom fatigue” will be on the shortlist for Oxford Dictionary’s 2020 Word of the Year, with the phenomenon well described by National Geographic, the BBC, and others. While I agree with many of the arguments about the physiological taxes video conferencing applications place on the body, they fail to acknowledge that virtual spaces can be informed by and redesigned like our physical spaces.

隨著我們在虛擬會議室中度過的時間越來越長,虛擬會議室的無趣設計變得越來越內臟。 毫無疑問,“縮放疲勞”將在《牛津詞典》的2020年度最佳單詞候選名單中出現,該現象在《 國家地理》 , 英國廣播公司和其他機構中都有很好的描述。 盡管我同意視頻會議應用程序對人體施加生理稅的許多論點,但他們沒有意識到虛擬空間可以像我們的物理空間一樣被告知和重新設計。

We’ve known for millennia that room design has profound effects on our sociability, productivity, creativity, spirituality, governance, and contentment. So if we are searching for greater fulfillment in our daily lives, we should stick a probe into room design itself to search for clues into how the spaces we inhabit affect our being. Our physical rooms have a lot to teach us about how we can improve our virtual ones.

幾千年來,我們已經知道,房間設計對我們的社交能力,生產力,創造力,靈性,治理和滿足感都有深遠的影響。 因此,如果我們要在日常生活中尋求更大的成就,就應該對房間設計本身進行探索,以尋找有關我們居住的空間如何影響我們的存在的線索。 我們的實體房間可以教給我們很多有關如何改善虛擬房間的知識。

Zoom, BlueJeans, WebEx and their brethren design virtual rooms for pure utility. Our video conferencing rooms have been stripped away nearly entirely of distractions, at the same time removing many of the aesthetic properties and layers of intentionality that characterize a compelling room. The Zoom “Personal Meeting Room” is a high density picture of nothing much; it at once leaves everything and nothing to the imagination. To pull a concept from David Brooks’ Second Mountain, video conferences are a “big box of possibilities” where often the promise is far greater than the results. Perhaps the blank nature of the applications is aspirational–merely providing a base for others to build upon. But the trouble with this model is that most hosts and participants struggle to create meaningful gatherings in the real world, and doing so in a virtual one is even harder. We approach Zoom like we do most of our gatherings–arriving with the blind hope that getting people into a room together is going to yield something magical. And we all know that is all too rarely true, right? It’s probably on the order of 10–20% of the meetings and gatherings that we participate in where we leave feeling like not only the time spent was worthwhile, but also that true human connection(s) were formed in the process.

Zoom,BlueJeans,WebEx和他們的弟兄為純實用程序設計虛擬房間。 我們的視頻會議室幾乎被所有干擾物所剝奪,同時消除了許多吸引人的房間的美學特征和意圖層。 Zoom“個人會議室”是一張高密度的圖片,僅此而已。 它一下子讓一切變得虛無。 為了從戴維·布魯克斯(David Brooks)的《 第二山 》( Second Mountain)中汲取靈感,視頻會議是一個“巨大的可能性”,其中的希望往往遠大于結果。 也許應用程序的空白性質是抱負,只是為其他應用程序提供了基礎。 但是這種模式的麻煩在于,大多數主持人和參與者都難以在現實世界中創建有意義的聚會,而在虛擬環境中進行聚會則更加困難。 我們像參加大多數聚會一樣對待Zoom,帶著盲目的希望,使人們聚在一起,會產生神奇的效果。 我們都知道這很少是真的,對吧? 我們參加的會議大概有10%到20%左右,我們離開的感覺不僅是值得的,而且在此過程中形成了真正的人脈關系。

In most ways the virtual rooms we join are entirely unfulfilling by standards of “memorable rooms.” As compared to our physical rooms, minimal attention is paid to the design of our virtual rooms by the application creators, nor how the room is set up by those convening the calls. Zoom Personal Meeting Rooms are blank canvases when we arrive, and equally blank when we exit. Perhaps part of the empty feeling that comes from spending time in these blank rooms comes from not only their lack of fulfilling design, but their transient, disposable existence, and the fact that we must mentally leave the more layered rooms we physically occupy and displace ourselves virtually to be fully present in the meager construct as alluded to in Part One. So part of the solution resides in remaining physically present in our own rooms while being virtually present in another one, but there is also an opportunity to think about how our Zoom rooms can be designed to embody some of the principles that make our offline rooms fulfilling spaces to gather.

在大多數情況下,我們加入的虛擬房間完全無法滿足“難忘房間”的標準。 與我們的物理房間相比,應用程序創建者對虛擬房間的設計沒有多少關注,而召集呼叫的人如何設置房間。 Zoom個人會議室到達時是空白的畫布,退出時同樣是空白的。 在這些空白的房間里度過的時間,空虛的感覺也許不僅是由于他們缺乏充實的設計,還因為它們短暫而隨意的存在,以及我們必須在精神上離開我們實際居住和移位的更分層的房間這一事實。幾乎完全存在于第一部分中提到的微薄結構中。 因此,解決方案的一部分在于保留物理上存在于我們自己的房間中,而實際上又存在于另一個房間中,但是也有機會考慮如何設計我們的Zoom房間,以體現使離線房間充實的一些原理。可以收集的空間。

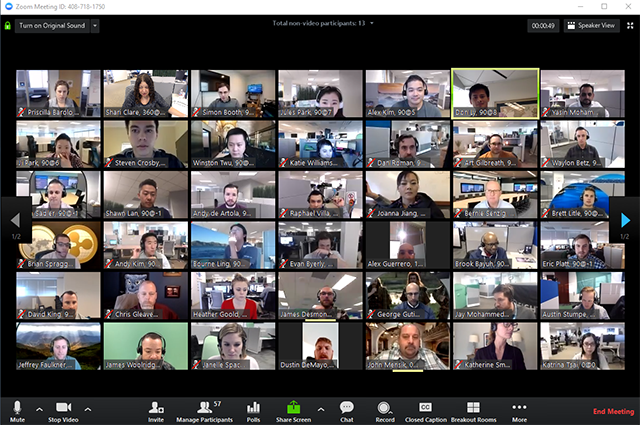

While it’s an impossible task to summarize all the ways that Zoom and other video conferencing applications are being deployed to bring groups together, the three layout views remain consistent on all gatherings: speaker, gallery, and mini. Everyone (including ourselves) is displayed in rectangular boxes. A Zoom room view can accommodate up to 49 participants viewable at one time. Regardless of the selected view, a Zoom Room is a room of rooms: a layout that situates the physical rooms of participants within a virtual room. This virtual room becomes the space for shared experience. Our video conferencing rooms do not have to be casualties of an antispatial and disembodied cyberspace. Instead, I propose we think of our virtual rooms as intentionally designed objects like our physical rooms — spaces where the design has profound effects on the outcomes of the gathering itself.

總結部署Zoom和其他視頻會議應用程序以將組聚集在一起的所有方式是一項艱巨的任務,但是在所有聚會上, 三個布局視圖仍然保持一致:演講者,畫廊和小型會議。 每個人(包括我們自己)都顯示在矩形框中。 縮放室視圖可同時容納多達49位參與者。 不管選定的視圖如何,“縮放室”都是一個房間的房間:一種布局,將參與者的物理房間放置在虛擬房間內。 這個虛擬房間成為共享體驗的空間。 我們的視頻會議室不必是反空間和無形的網絡空間的犧牲品。 相反,我建議我們將虛擬房間視為像物理房間那樣的故意設計的對象,在這些空間中,設計對聚會本身的結果產生深遠的影響。

意向設計室 (Rooms of Intentional Design)

In her essay, How Room Designs Affect Your Work and Mood, Emily Anthes tells the story of how the polio vaccine may never have happened had it not been for Jonas Salk awakening to the fact that the place where he was doing all his invention at the time, a basement laboratory, was constraining his creativity.

艾米莉·安特斯(Emily Anthes)在她的論文《房間設計如何影響您的工作和情緒》中講述了如果喬納斯·索爾克(Jonas Salk)并非意識到自己在麻省進行所有發明的地方,脊髓灰質炎疫苗可能永遠不會發生的故事。那時,地下室的實驗室限制了他的創造力。

In the 1950s prizewinning biologist and doctor Jonas Salk was working on a cure for polio in a dark basement laboratory in Pittsburgh. Progress was slow, so to clear his head, Salk traveled to Assisi, Italy, where he spent time in a 13th-century monastery, ambling amid its columns and cloistered courtyards. Suddenly, Salk found himself awash in new insights, including the one that would lead to his successful polio vaccine. Salk was convinced he had drawn his inspiration from the contemplative setting. He came to believe so strongly in architecture’s ability to influence the mind that he teamed up with renowned architect Louis Kahn to build the Salk Institute in La Jolla, Calif., as a scientific facility that would stimulate breakthroughs and encourage creativity.(7)

在1950年代,屢獲殊榮的生物學家和醫生喬納斯·索爾克(Jonas Salk)在匹茲堡一個黑暗的地下室實驗室中治療小兒麻痹癥。 進展緩慢,因此,Salk清醒了頭腦,前往意大利的阿西西(Assisi),在那里他在一座13世紀的修道院里度過了一段時光,在它的圓柱和隱蔽的庭院中漫步。 突然,薩爾克(Salk)發現自己陷入了新的見解,包括將導致他成功的脊髓灰質炎疫苗的見解。 薩爾克深信他是從沉思中汲取靈感的。 他開始堅信建筑具有影響思想的能力,于是他與著名的建筑師路易斯·卡恩(Louis Kahn)合作在加利福尼亞州拉霍亞建立了薩爾克研究所(Salk Institute),這是一個科學設施,可以激發突破并鼓勵創造力。(7)

While part of the breakthrough for Salk could be attributed to a change of context, the rooms of the Assisi monastery and its relationship to external spaces had profound effects on Salk’s creativity. And most of us understand this at a gut level. We draw a curtain back to reveal more light. We head to the coffee shop for the ambiance. We go to a retreat centre for inspiration. The architecture of space clearly affects our lived experiences within them. For anyone who has visited the Salk Institute in San Diego, Fallingwater outside Pittsburgh, or the Bauhaus in Dessau, it is nearly impossible to avoid being spirited away by the spaces. And so it is all the more shocking that there seems to be a general negligence in the virtual room architecture of our video conferences.

雖然薩爾克(Salk)的部分突破可以歸因于環境的變化,但阿西西修道院的房間及其與外部空間的關系對薩爾克(Salk)的創造力產生了深遠影響。 而且我們大多數人都從直覺上理解這一點。 我們拉開窗簾以露出更多的光。 我們前往咖啡廳尋求氛圍。 我們去一個靜修中心尋求靈感。 空間的體系結構顯然會影響我們在其中的生活體驗。 對于參觀過圣地亞哥的Salk研究所,匹茲堡外的Fallingwater或德紹的包豪斯的人來說,幾乎不可能避免被這些空間所吸引。 因此,令人震驚的是,視頻會議的虛擬會議室架構似乎普遍存在疏忽。

As I was thinking about the architecture of virtual rooms, I was pleasantly surprised to stumble upon an ode to room design in The New York Times Style Magazine, The 25 Rooms That Influence the Way We Design. Before short-listing the rooms, the six-person jury has to first discuss the benign but essential question, “what is a room?” and then determine why certain rooms exert influence.

當我在思考虛擬房間的體系結構時,我很驚訝地偶然發現《紐約時報風格》雜志 “影響我們設計方式的25個房間”中對房間設計的頌歌。 由六人組成的陪審團在篩選房間之前,必須首先討論良性但必不可少的問題:“什么是房間?” 然后確定為什么某些房間施加影響。

Tom Delavan: My colleague Kurt and I were discussing what qualifies as a room, and we thought, “Well, a room has walls, or something that could define a wall.”

湯姆·德拉文(Tom Delavan) :我的同事庫爾特(Kurt)和我正在討論什么才是合格的房間,我們認為,“好,房間有墻,或者可以定義墻的東西。”

Simon Watson: For me, a room is a place for people to inhabit together in solidarity, I suppose…It’s a place where people can gather; it’s what we humans do.

西蒙·沃森(Simon Watson) :對我來說,一個房間是人們可以團結在一起居住的地方,我想……這是人們可以聚集的地方。 這就是我們人類所做的。

Gabriel Hendifar: Or is it just about some spatial organization that communicates intention, whether that intention has a ceiling or not? A room is something that’s been organized to serve some function, whether that is spiritual or shelter, residential or commercial.

加布里埃爾·亨迪法(Gabriel Hendifar) :還是只是一些傳達意圖的空間組織,無論意圖是否有上限? 房間是為了某種功能而組織的,無論是精神上還是住所上,住宅上還是商業上。

Toshiko Mori: Well, also, Stonehenge has a reference to astronomy. It’s [sic] human enclosure, with references to the world outside earth. So, the ceiling in this case is a sky. I think that’s the beauty with it, that it actually exists between ground and sky.

森敏俊(Toshiko Mori) :嗯,巨石陣也提到了天文學。 這是人類的封閉空間,指的是地球以外的世界。 因此,這種情況下的天花板是天空。 我認為這就是它的美,它實際上存在于地面和天空之間。

While I agree that a room is defined as a delimited space by physical structure(s) and functional intention, I disagree that a room can be defined solely by the spatial organization of people. Let’s take the prototypical village image of a community gathered in a circle, usually around a campfire. It’s spatial by the arrangement of the people, but I think we can all agree that it is not a room. A room needs spatial boundaries that define interiority. Without the ability to define whether you are inside or outside a room, there is no room at all, just space.

雖然我同意通過物理結構和功能意圖將房間定義為界定的空間,但我不同意只能由人的空間組織來定義房間。 讓我們以一個社區的原型村莊形象為例,這個社區通常圍著篝火圍成一圈。 它是由人們的安排決定的空間,但是我認為我們都可以同意這不是一個房間。 房間需要定義內部空間的空間邊界。 無法定義您是在房間內還是房間外,根本就沒有房間,只有空間。

As I waded through the twenty-five rooms selected by The New York Times jury and their justification for the selections, I could not help but feel like we were missing a massive opportunity for better architecture of our virtual rooms. We have large data sets on the influence of architectural decisions on human behaviour in public and private spaces, and yet little of this thinking and analysis seems to have been applied to our virtual rooms. Forgive me, for I am not an architect, but there were a few architectural concepts that stood out to me from the NYT jury’s selected physical rooms that I think can provide guidance towards more fulfilling virtual rooms. Hopefully you find them inspiring as well.

當我仔細閱讀《紐約時報》陪審團選定的25個房間及其選擇的理由時,我忍不住感到好像我們錯過了一個更好的虛擬房間架構的巨大機會。 我們擁有關于建筑決策對公共和私人空間中人類行為的影響的大量數據集,但這種思想和分析似乎很少應用于我們的虛擬房間。 原諒我,因為我不是建筑師,但是從NYT評審團選擇的實體房間中,有一些建筑概念對我很突出,我認為這些概念可以為更充實的虛擬房間提供指導。 希望您也能激發他們的靈感。

內部/外部 (Interiority/Exteriority)

Whether it is the ability to see the sky by looking up at Stonehenge or from within the Pantheon, or the way to see out with the garden facing design of the Shokin-tei tea pavilion and the Teshima Art Museum, the ability to be both inside a room and conscious of the outside at the same time–to see differently–is what makes these rooms remarkable. This relationship places a room in space and creates a porousness where the inside feels richer by framing perspectives on what is outside the room. According to a study by environmental psychologist Nancy Wells, rooms that provide views of natural settings empirically improve focus.(8)

無論是通過仰望巨石陣或從萬神殿內部觀看天空的能力,還是通過Shokin-tei茶館和Teshima美術館的面向花園設計的視野,都可以在內部觀看的功能一個房間并同時注意外部(換個角度看)是使這些房間與眾不同的原因。 這種關系將房間放置在空間中,并通過在房間外部構筑透視圖,從而使內部感覺更加豐富。 根據環境心理學家南希·韋爾斯(Nancy Wells)的一項研究,可以看到自然環境的房間從經驗上提高了注意力。(8)

Could we have a relationship between interiority and exteriority in our Zoom rooms? Sure, we could. While our Zoom rooms now are singular spaces, why not have adjacent spaces of contemplation, engagement, and inspiration that simultaneously exist alongside the current room? To some extent the breakout rooms of Zoom are the closest thing the application has to adjacent spaces. However, breakout room design remains entirely unchanged despite a shifting purpose. And our only current way to see out of our Zoom rooms is to turn away from the screen.

我們的Zoom房間能否在內部和外部之間建立聯系? 當然可以。 雖然我們的Zoom房間現在是單數空間,但為什么不存在與當前房間同時存在的相鄰的沉思,參與和靈感空間? 在某種程度上,Zoom的突破空間是應用程序與相鄰空間最接近的空間。 然而,分組討論室的設計盡管用途有所變化,但仍保持完全不變。 目前,我們從Zoom會議室中看到的唯一方法就是遠離屏幕。

模塊化 (Modularity)

After Jean-Fran?ois Lemoine was in a car crash that left him with limited mobility, Rem Koolhaas & OMA designed an elevator office for Lemoine’s home in Bordeaux. The interior core of the house, forever set up as an office, ascends and descends to fit perfectly into any of the three floors. And with a modular core, the room changes shape and function depending on where the elevator platform resides.

讓-弗朗索瓦·勒莫因(Jean-Fran?oisLemoine)發生車禍后,行動不便,雷姆·庫哈斯(Rem Koolhaas)和OMA為勒莫因在波爾多的家設計了一個電梯辦公室。 房子的內部核心(永遠設置為辦公室)會上升和下降,以完美地適合三層樓中的任何一層。 借助模塊化核心,房間可根據電梯平臺所在的位置改變形狀和功能。

By thinking of a room as a series of building blocks, we can imagine new spaces of modularity within our virtual rooms. In fact, the Zoom grid is already a modular construct with each participant framed in their respective rectangles. What if we deployed a few of those rectangles in the grid for something other than participant headshots? Certain rectangles could change, ascend, or descend at different moments of the call with images or videos that create inspiration, context, and meaning for our conversations. Our Zoom rooms could become uniquely designed for each call, and bring the kind of modularity of space OMA evoked in the physical Lemoine home with the elevator office.

通過將房間視為一系列構建模塊,我們可以想象虛擬房間中模塊化的新空間。 實際上,“縮放”網格已經是一種模塊化結構,每個參與者都以各自的矩形框起來。 如果我們在網格中為參與者頭像以外的其他內容部署了一些矩形,該怎么辦? 某些矩形可能會在通話的不同時刻發生變化,上升或下降,而圖像或視頻會為我們的對話創造靈感,上下文和含義。 我們的Zoom室可以針對每個呼叫進行獨特的設計,并帶來帶有電梯辦公室的實體Lemoine住宅中喚起的OMA空間模塊化。

文物 (Artefacts)

For many rooms what gives them interest is the artefacts selected for the interior and the arrangement of them. Whether it is the flea market procured antiquities of Cy Twombly’s apartment in Rome or the pool in Philip Johnson’s Four Seasons Dining Room, artefacts become objects of attention and surfaces of sensemaking. And yet rarely are artefacts visible in our Zoom rooms. Or if there are artefacts present, they are often too small to draw our attention.

對于許多房間來說,使他們產生興趣的是為其內部和布置選擇的人工制品。 無論是跳蚤市場上采購的Cy Twombly在羅馬的公寓還是菲利普·約翰遜(Philip Johnson)的“四個季節的餐廳”中的游泳池等古董,手Craft.io品都成為人們關注和感性的對象。 但是,在我們的Zoom房間中幾乎看不到任何人工制品。 或者,如果存在文物,它們通常太小而無法引起我們的注意。

Perhaps you’ve already been on a video conference where physical artefacts have been shared as part of the proceedings. By introducing our own personal artefacts or those provided by the room host for the group, a Zoom room can be transformed from its prior emptiness into one that spurs reflection or evokes history, culture, and expression.

也許您已經參加過電視會議,在會議中分享了人工制品。 通過介紹我們自己的私人手Craft.io品或房間主持人為小組提供的人工手Craft.io品,可以將Zoom Room從其先前的空虛狀態轉變為刺激反射或喚起歷史,文化和表達的空間。

I only use these examples above to suggest some of the massive possibilities that await more intentionally designed virtual spaces, especially by those with the well-honed talents of designing spirited human spaces in the physical world. This is the beginning of a conversation that I hope will gain momentum.

我僅使用以上示例來說明一些等待更故意設計的虛擬空間的巨大可能性,特別是那些擁有在物理世界中設計充滿活力的人類空間的高才人才。 我希望這是對話的開始,希望會有所發展。

意識的房間 (Rooms of Consciousness)

With all that can be explored in the spatial design of our virtual rooms, we need not depend on their architecture alone to animate the creativity of our participants. The animating force can also come from the state of consciousness that is created during the video conference itself.

在我們虛擬房間的空間設計中可以探索的所有事物中,我們不必僅僅依靠它們的建筑來激發參與者的創造力。 動畫效果還可以來自視頻會議本身產生的意識狀態。

In his essay “The Storyteller” Walter Benjamin laments an end to the art of storytelling; we have lost the ability to exchange experiences with one another by abandoning our oral traditions. Stories should arouse “astonishment and thoughtfulness” by “having counsel”(9)–conveying usefulness in the practical and open-ended form of a moral or maxim.

沃爾特·本杰明(Walter Benjamin)在他的論文《講故事的人》中感嘆講故事藝術的終結。 我們放棄了口頭傳統,失去了彼此交流經驗的能力。 故事應該通過“請顧問”(9)引起“驚訝和體貼” —以實用或開放的道德或格言形式傳達有用性。

I am sure many could argue that their bullet points on a shared Zoom screen are “practical,” but they are rarely delivered in a way that provokes individual interpretation and creativity. We tend to approach our video conference meetings much as we would our in-person ones with clear desired outcomes and an agenda that helps us get from A to B. Benjamin’s point is that by approaching our gatherings linearly, we forgo the opportunity for greater meaning to be created. The conditions for reception, not just the agenda, must also be right.

我敢肯定,許多人可能會爭辯說,他們在共享的“縮放”屏幕上的要點是“實用的”,但很少以引起個人解釋和創造力的方式來交付它們。 我們傾向于視頻會議的方式與面對面的會議一樣,希望取得清晰的預期結果,并制定有助于我們從A到B的議程。Benjamin的觀點是,通過線性方式進行聚會,我們放棄了更大意義的機會被創建。 接待的條件,不僅是議程,也必須是正確的。

This process of assimilation, which takes place in depth, requires a state of relaxation which is becoming rarer and rarer. If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. A rustling in the leaves drives him away. His nesting places — the activities that are intimately associated with boredom — are already extinct in the cities and are declining in the country as well. With this the gift for listening is lost and the community of listeners disappears. For storytelling is always the art of repeating stories, and this art is lost when the stories are no longer retained.(10)

深度發生的這種同化過程需要放松的狀態,這種狀態變得越來越少。 如果說睡眠是身體放松的最高境界,那么無聊就是精神放松的最高境界。 無聊是孵化經驗之卵的夢想鳥。 葉子里沙沙作響的聲音驅趕了他。 他的巢穴-與無聊息息相關的活動-在城市已經絕種,并且在該國也正在減少。 這樣一來,聆聽的天賦就消失了,聽眾社區也消失了。 因為講故事總是重復故事的藝術,而當不再保留故事時,這種藝術就會消失。(10)

Much like the bird sitting on its nest, we need boredom in order to reflect upon, assimilate, and retain the wisdom within the story told to us. In the case of video conferences, time is often our enemy and silence the grim reaper. We are rushed to get through agendas and feel it a necessity as host to fill in any blanks that may happen on a virtual gathering. Contrary to our intuition and discomfort, there are transformative experiences to be had by slowing down the pace of our video conferences (alongside great storytelling, of course) in order to stimulate active listening.

就像坐在鳥巢上的小鳥一樣,我們需要無聊才能反思,吸收并保留告訴我們的故事中的智慧。 就視頻會議而言,時間通常是我們的敵人,而沉默無能。 我們急于通過議程,并感到有必要作為主持人來填補虛擬聚會中可能發生的任何空白。 與我們的直覺和不適相反,放慢視頻會議的速度(當然還有出色的講故事),以激發積極的聆聽,可以帶來變革性的體驗。

Just like designing a room in the physical world, designing it in the virtual one is inherently a creative act. While design decisions of what is in a room and how that room functions are often overlooked in our video conferences, the stakes for these decisions are high. If we are to create virtual gatherings that do more than produce–that transform our relationships, governments, businesses, public organizations, and education institutions–we need to deploy a wider toolset. By looking to the principles of the great rooms in our lives and the temperaments by which we approach our engagement within them, we can encourage more of the creativity, innovation, inclusion, and culture change that we seek.

就像在物理世界中設計房間一樣,在虛擬環境中設計房間本質上是一種創造性的行為。 在我們的視頻會議中,盡管經常會忽略關于房間中的內容以及房間功能如何的設計決策,但這些決策的風險很大。 如果我們要創建虛擬的聚會,而不僅僅是聚會,可以改變我們的關系,政府,企業,公共組織和教育機構,則我們需要部署更廣泛的工具集。 通過關注生活中大房間的原則以及我們與之互動的氣質,我們可以鼓勵我們尋求的更多創造力,創新,包容性和文化變革。

This concludes Part Two of a four–part essay. I hope you will join me for Part Three where I explore how we can author history and meaning in our Zoom rooms with a few of the practical management tips you might have been hoping for all along.

至此,全文分為四部分。 我希望您能與我一起參加 第三部分 ,在這里我將探討我們如何在Zoom室中編寫歷史和意義,以及您一直以來一直希望得到的一些實用管理技巧。

尾注 (Endnotes)

(7) Emily Anthes, “How Room Designs Affect Your Work and Mood”, Scientific American, April 2009.

(7)艾米莉·安特斯(Emily Anthes),“ 房間設計如何影響您的工作和情緒 ”,《 科學美國人》 ,2009年4月。

(8) Ibid.

(8)同上。

(9) Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (Schocken Books, 1998), 86.

(9)沃爾特·本杰明(Walter Benjamin),《 照明》 (Schocken Books,1998年),第86頁。

(10) Ibid, 91.

(10)同上,91。

翻譯自: https://uxdesign.cc/part-two-humanizing-the-spaces-of-video-conferences-zoom-et-al-704497aba2f1

zoom視頻會議官網

本文來自互聯網用戶投稿,該文觀點僅代表作者本人,不代表本站立場。本站僅提供信息存儲空間服務,不擁有所有權,不承擔相關法律責任。 如若轉載,請注明出處:http://www.pswp.cn/news/275605.shtml 繁體地址,請注明出處:http://hk.pswp.cn/news/275605.shtml 英文地址,請注明出處:http://en.pswp.cn/news/275605.shtml

如若內容造成侵權/違法違規/事實不符,請聯系多彩編程網進行投訴反饋email:809451989@qq.com,一經查實,立即刪除!

會殺死導航抽屜嗎?)

)

中奇怪的一項功能)